By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, Magazine, Edition 10. June 16th 2014

Introduction

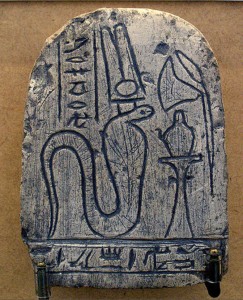

Figure 1. Meretseger as a cobra, with plumed head-dress. Her name “she who loves silence” is clearly shown in the vertical column. Photograph by Su Bayfield. Turin cat. 1519 / CGT 50001

In the Western world the cobra rarely inspires sentiments of hospitality, tranquility or warmth. It bites, which is never a good sign, and the accompanying venom can cause blindness or respiratory problems that may result in death. Unsurprisingly, we tend to regard the cobra with a level of caution entirely appropriate to the injury that it is capable of inflicting. Matters were more ambivalent in ancient Egypt where a range of wild and often fierce animals were identified with deities who were imbued with admired values of physical strength, fearlessness and courage, as well as less obviously admirable qualities such as aggression, ferocity and power. In Egypt these harsher features translated into concepts like protection, retribution, vengeance and retaliation. Like Sobek, the crocodile deity, Sekhmet the lioness and Hathor in her guise as the vengeful weapon of Ra, the cobra deities comprised a mixture of attributes that centred on their formidable ability to defend themselves and to strike, hissing and spitting poison, to annihilate their aggressors.

Wilkinson lists eleven serpent deities, of which the best known is the cobra goddess Wadjet, who guarded the king from her position at the front of his crown and watched over his mortal remains with her fabulous wings outspread. But there were two other important serpent goddesses of Egypt named Renenutet, who oversaw cultivation and grain, and and Meretseger (or Merseger) who had a special place in the lives of the villagers of Deir el Medina.

Meretseger was never worshiped beyond western Thebes. And although she was the guardian of the necropolis of the New Kingdom kings, she only rarely appears in the tombs she protected. Instead, she was venerated by the builders and decorators of the Pharaonic tombs mainly during the 19th and 20th Dynasties. Whilst the deified 18th Dynasty Amenhotep I was the main god of the tomb workers of Deir el-Medina, other deities were worshiped as well, commemorated in the stelae and ostraca that were left in the small shrines dedicated to them. These often lovely objects were the means by which everyday people were able to invest in small but important statements of personal piety, and they demonstrate that Meretseger was an important deity in the village. Although she is never shown in the workers’ tombs, she was clearly important to them. Sometimes it is through the lesser known deities that we can see beyond the royal court, into the lives of those who are always less visible in the archaeological record.

Deir el Medina was the village of the royal tomb workers and their families, a tight-knit but occasionally volcanic community of people who lived in somewhat extraordinary circumstances (figure 2). It was built by Tuthmosis I near to where the tombs were to be constructed on the edge of the desert, and was called The Place of Truth. Whether or not these lives can be considered to be in any way typical of those in rural or suburban villages along the Nile is impossible to judge, but they do provide an insight into an isolated but vibrant community, a machine within a machine, with its own hierarchies of value, and its own social stratigraphy. One of the many unusual aspects of Deir el Medina is that small aspects of the lives of villagers are recorded on stelae and ostraca, capturing thoughts as they were articulated by real people with real-world concerns.

From the Middle Kingdom onwards personal stelae were dedicated to Osiris and a new trend of personal piety emerged. By the New Kingdom the vast temple estates managed by priests still served a core religious and economic role in the state system, but ordinary people were also now conferring with the gods on their own terms. In addition to the major deities like Amen-Ra, there was a growth in the popularity of minor deities who were usually confined to cult centres are are rarely found further afield. At Deir el Medina a variety of gods were worshiped, including Amun, Hathor, Ptah, Thoth, Taweret, Sobek, Bes, Seth, the deified Amenhotep I, and Meretseger. Worship of Osiris and Isis was confined mainly to tombs. Temples were erected to Amen-Ra, Hathor and Amenhotep I and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari. Small chapels were also erected, and a sanctuary to Ptah and another to Ptah and Meretseger were built on the route to the Valley of the Queens (figure 4). The slopes of El Qurn were covered in shrines. Penitential texts were now common, and there was clearly a sense amongst the villagers that gods were influential, judgemental and vengeful, but could also grant favours, forgive mistakes and reverse punishments. There is an an implied acknowledgement of human frailty in these texts, and a sense of intimacy and dialogue with the gods that the villagers clearly valued. In this new panorama of personal piety, the essence of a god is that he or she may be spiritually present at all times, may be watching and may be listening. Other forms of worship were also practiced at Deir el Medina, including employment of an oracle (a physical representation of a deity who could be petitioned) and a form of ancestor worship, in which the deceased were labeled as “excellent spirits of Ra.” All of these different cults seem to have lived in perfect harmony with each other. There was no priesthood to administer them; instead they were managed by the villagers themselves.

The gods favoured were sometimes very easy to understand as natural companions to the villagers: Hathor was associated with motherhood, women and fertility, Amen-Ra was the nation’s supreme deity and supporter of the poor, Thoth was special to scribes, Ptah was the patron of craftsmen but also had an important role in the matter of justice, Tawaret had a special connection with women, as did Bes, and Amenhotep Iwas probably connected by the villagers to the origins of their community, although the village itself was established by Tuthmosis I. As men were absent from the village between 9 and 10 days at work, women were left to run the village and many of the deities were female protectors. Others are less easy to comprehend. Khnum and his consort were popular, but they were local to far-off Elephantine (modern Aswan) and a number of foreign gods were also worshiped.

Representations and iconography of Meretseger

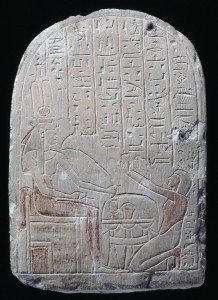

Meretseger was of great importance to the villagers, but it is by no means easy to characterize her. Her name, mrtsgr or mrsgr, can be translated as “she who loves silence” (figure 1). Images of Meretseger appear on stelae, rock cut shrines and ostraca. Meretseger is usually shown on her own, but may also be accompanied by other deities worshiped at Deir el Medina, about which more below. These dedications are all fairly small and relatively simple, and are often quite basic in design and execution, although there are notable exceptions, some of which are shown in this article. The stelae tend to be more elaborate in terms of both size and composition, but many painted ostraca (small, roughly shaped pieces of pottery or stone) are remarkably fine as well.

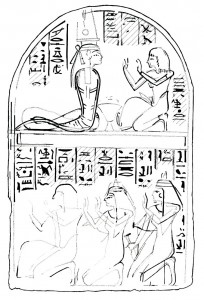

Figure 5. British Museum stela EA371 showing Mertseger as a rearing cobra with the head of a woman, praised by Penpahapi and his family. Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum

Like many other localized deities Meretseger is closely associated with the topographical features of the place from which she derived. Meretseger was identified with, and often referred to as Peak of the West (dhnt imntt) the al-Qurn pinnacle above the Valley of the Kings, which has a roughly pyramidal shape (figure 4). It was thought to be one of the entrances to the netherworld, as well as the place where Meretseger resided. As well as the Peak of the West she was also referred to more generally as Mistress of the West (Hnwt imntt), Mistress of the Beautiful West, Mistress of the Gods (Hnwt nTrw) and Lady of Heaven (nbt pt), all of which are shown on the Stela of Nebnefer.

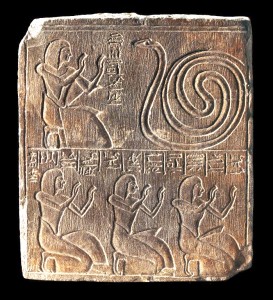

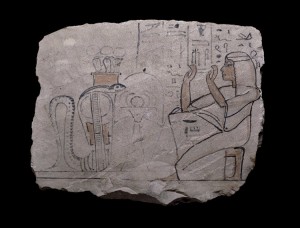

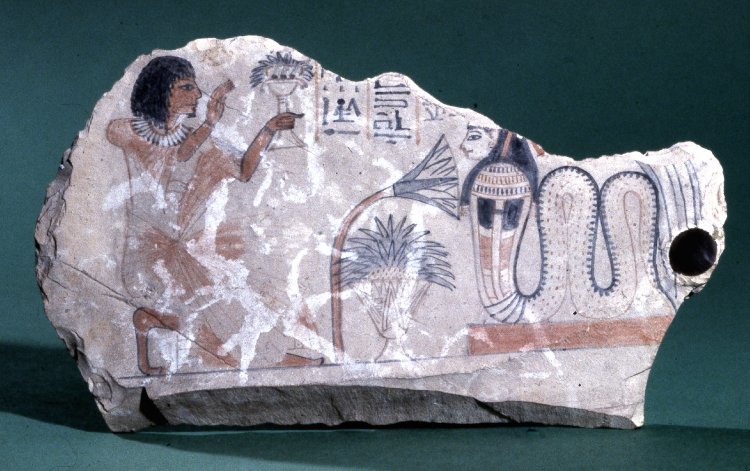

Although by far the greater number of depictions of Meretseger are based on the serpent theme, there is considerable variation in how she is represented. She was variously shown as a woman (figure 7), a cobra curling along the ground (figures 1, 6 and 13), a cobra with a woman’s head (figure 5), a cobra as a fully extended snake (figure 8), a coiled serpent (figure 9), a woman with a cobra’s head (figures 11, 12) or, more unusually, with the head of a vulture. Some representations combine different aspects of her. The Petrie Museum’s ostracon UC14439 (figure 6) shows her as a cobra curving along the ground, her hood expanded with two smaller snakes emerging from where her rearing head rests on the ground. Similarly, Neferabu’s stela to Meretseger shows her as a woman-headed cobra, with a serpant rising from one side of her body, a vulture-headed serpent from the other (Turin 102 / 50058).

Very few Egyptian deities were represented in just one form. Each different form of a deity is usually associated with the different myths connected with them. There are, unfortunately, no myths associated with Meretseger. There are no stories about her life amongst the gods, and very few indications of relationships with other gods. The different ways of representing Meretseger could well be a simple matter of personal preference, or chosen to display those characteristics to which an individual was appealing under specific circumstances. Meretseger appears to be at her most generic, as an undifferentiated serpent, when the prayers offered are themselves somewhat generic efforts to win the good will of the goddess for unspecified reasons, like that of the lady Wab below (figure 8). At her most elaborate, with complex iconography, Meretseger may be associated with rather more personal and specific requests for forgiveness and assistance. Neferabu’s account of how Meretseger punished him but returned to forgive and cure him (Turin 102/50058) is an example of these detailed requests for help, and the three-headed serpent was amongst the most complex representations of the goddess. Of course, not all fall so neatly into these convenient categories and it is more than likely that there were many other ideas at play. Deir el Medina was occupied by the tomb workers and their families for over 400 years and it is entirely possible that perceptions of her changed during that period.

On her head Meretseger is usually adorned with a solar disk topped with twin plumes (figures 1 and 6) or, more rarely,with a solar disk contained within cow’s horns in a style reminiscent of one of the crowns of Hathor (figure 11). More unusual examples also exist. In ostracon EA8510 from the British museum, for example, Meretseger wears a crown topped by a row of three rearing cobras, which with a solar disk on its head (figure 10).

Offering tables are often shown in scenes where Meretseger is depicted. These are invariably fairly simple, containing one or more vessels and few other accoutrements. A vessel that appears regularly on the table is something that looks remarkably like a teapot, the nemset libation vase (see figures 1 and 7) with spout and lid and was probably used for purification rituals. Other vessels, tall and thin, are sometimes shown underneath the table. A recurrent theme is the lily either on the table, over the table or over the head of Meretseger. The water lily was the symbol of creation, rebirth, rejuvenation and healing and appears frequently on New Kingdom offering scenes.

The Role of Meretseger in the Lives of the Villagers

A dialogue with a deity says something about what the initiator of the conversation needs or expects from the deity. The individuals who worshiped Meretseger developed a very special relationship with her, and her importance in Deir el Medina suggests that she had a role not covered by other better-known deities.

A rectangular stela dedicated to Meretseger by the artist Neferabu provides the best known insight into her role as a deity who took an active interest in the moral rectitude of the villagers. The stela (Turin 102/ 50058) shows her on the right side of the scene as a serpent looking left over an offering table, with one human head and, from her chest a vulture head and neck and from her rear shoulder a serpent head and neck. On her head is a crown of twin plumes set over a solar disk. Translated by Miriam Lichtheim, the text describes how Neferabu had transgressed in some unspecified way “[I was] an ignorant man and foolish who knew not good from evil.” Neferabu was punished with some sort of malady, and appealed to Meretseger, whom he refers to as “the peak” for forgiveness and she came to him “as sweet breeze” and was merciful: “She made my malady forgotten.” He concludes, however, indicating that she was not to be trifled with: “Behold, let every ear that lives upon earth beware the Peak of the West!” This was not Neferabu’s first appeal to the gods for mercy. An earlier stela inscribed by Neferabu (BM 589), dedicated to Ptah, translated by Dan Potter says “I am a man who swore falsely by Ptah, Lord of Truth – he caused me to see darkness by day.” Ptah and Meretseger were closely related, sometimes appearing on the same stelae, and it is likely that the overlap in their function was all to do with their roles in the assurance of justice and retaliation.

A similarly themed stela from Deir el Medina is scribe Amennakht’s prayer to Meretseger “Mistress of the West.” In this 20th Dynasty stela she is shown as a woman with crown composed of a solar disk flanked by two plumes (British Museum EA354, figure 6). Amennakht is shown in a distinctive position on his knees, his arms raised to her. Amennakht offers prayers, perhaps for the restoration of his sight when she had made him “see darkness in the day.” Both Meretseger and Neferabu are shown without eyes, probably a reference to Meretseger’s power of depriving people of their sight. He promises to spread the word of her power to others. Her power to punish and forgive is clearly not in doubt, and Amennakht’s belief in her power to grant mercy and alleviate his symptoms is very real. For the scribe, the ability to converse directly with the goddess had offered the solution to his problems. Deities in the lives of the villagers may have been invisible, but they were far from abstract.

In another example, the foreman Khonsu from Deir el Medina stands with a group of other workmen and the Vizier To, praying to Meretseger. As one of two village foremen, a position inherited from his father Nekhenmut, Khonsu was responsible for the creation of a number of tombs for the sons of Ramessess III and was a leading figure at the village, but had not always managed to avoid trouble. His drunkenness is noted in an account of the accidental breaching of an earlier tomb during the construction of a new one, and he ran into trouble during the period of food shortages when he took a stand against the Vizier To, attempting to incite his workers to demonstrate against the visiting vizier during the 25th year of the reign of Ramesses III in the 19th Dynasty. The dedication of Khonsu and his companions on the rock-cut stela appeals to Meretseger’s good will without specifying any wrong-doing for which forgiveness might be required, and it is possible that Khonsu’s motives in depicting himself both with To and with some of his workers were political as well as religious, and perhaps he hoped that Meretseger would smooth his path at work.

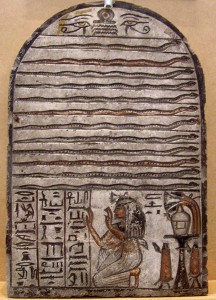

A 19th Dynasty stela of Nebnefer, left in a cave on the outskirts of the village, shows another different way of representing the goddess (figure 8). Here a lady, identified in the text as “lady of the house of Wab,” the wife of Nebnefer, kneels at the bottom of the stela while 12 serpents are shown above her, all facing right, clearly identified in the text. There are no pleas for forgiveness. Her stela is a dedication, a votive offering, a means of finding favour with an influential deity rather than trying to reverse a punishment already handed out. The lady Wab is actually mAa hrw, justified or, more literally, “true of voice”, meaning that she is dead. The dedication was made on her behalf, probably by her husband Nebnefer. Perhaps Wab had felt a particular affinity with Meretseger during her life, or perhaps her family merely wished to ensure the offices of a powerful deity and notoriously just deity. Behind her head is the phrase m Htp “at peace.” The wadjet eyes, symbols of regeneration and protection, and the shen symbol of eternity oversee the vignette below, in which the usual wishes for the dead are added at the end of the main inscription: life, strength, health, for the ka of the mistress of the house Wab, justified. This is very different from the penitent and thankful texts that refer to specific acts of retribution, but it still indicates that Meretseger was someone to be considered when matters were of sufficient importance, and that she required praise and pacification.

Figure 9. Paneb and family members worshiping Meretseger. BM EA 272. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

The foreman Paneb had every reason to have an eternally guilty conscience, and could probably have done with all the goodwill he could get from the deities, because he was something of a scoundrel. According to a document surviving from the time, he was guilty of a list of crimes that included bribery, misuse of workers, robbery of a royal tomb, the theft of state tools, forcible seduction and corruption. As Joyce Tyldesley put it in her book Judgment of the Pharaohs, Paneb was an “all round bad guy.”We have a short article about him on Egyptological, which demonstrates just why he might have been in need of a bit of timely divine intervention. Paneb dedicated a stela to Meretseger with his son and accomplice Aapakhte, and Aapakhte’s two sons Paneb and Nebmehyt. In the upper register of the 19th Dynasty stela Paneb is shown worshiping a coiled snake and in the lower register Aapakhte, Paneb junior and Nebmehyt are all shown in the act of worship (figure 9). Paneb dedicated at least one more stela to Meretseger, which is now at the British Museum (BM EA 273) and shows Paneb with his sons Aapakhte and Hednakht worshiping Meretseger seated on a throne with a woman’s body and serpent’s head. Here Meretseger has a human body with a cobra’s head, seated on a throne and she is clearly named in the text as “Merseger Mistress of the West.”

The ostrakon of Khnummose shows the workman on the right worshiping Meretseger in the form of a hooded cobra, who faces him on the opposite side of an offering table. Her crown is topped with three hooded cobras, each with a solar disk on their heads (figure 10). The text accompanying the beautiful little scene does not specify any particular request and instead, Khnnummose simply seems to be attempting to win the good favour of the goddess.

Meretseger does not appear on tomb walls, either in person or in texts. Although she might watch over the dead, she was not seen as an essential part of their transition into the tomb and beyond, suggesting that she was considered less important in death than she was in life, where she could intercede to make the living more comfortable.

Meretseger had the power to respond to appeals for good luck, mercy, clemency and forgiveness, to smooth the paths of those who requested her assistance and to reverse punishments that she had already imposed upon the guilty. The dedications made by the villagers amount to persuasion and coercion, but there is never a sense that these devotions will guarantee the hoped-for response. There is always the chance that the deity, forever a mixture of positive and more negative qualities, will refuse to act in favour of the plaintive. Offerings, dedications and prayers can only hope to influence the deity’s more generous side. She seems to have represented a form of localized justice, fairness and upright moral values. In short, she was a righteous deity, with whom many of the villagers had a very real relationship, and to whom they could address their hopes and fears.

Where she could not protect the tombs from thieves, and when she observed other wrong-doing, she was swift in her vengeance, inflicting poisonous stings, bites, and and various maladies upon those who committed sins. Prayers and offerings for forgiveness might be rewarded with ailments being alleviated or cured. Many penitential stelae fail to specify the misdemeanour for which punishment has been so swiftly meted out, but blasphemy and impiety appear to have been amongst the crimes committed.

Meretseger in the Company of other Deities

As listed above, other deities were worshiped by the villagers, and Meretseger was represented alongside some of them, including Amen-Ra, Ptah, the deified Amenhotep I and the hippopotamus goddess Taweret. She is also sometimes identified with Renenutet, and although Renenutet was associated with grain and agriculture, she was also concerned with security and well-being. .

Along the path from Deir el Medina to the Valley of the Queens were several shrines dedicated to Ptah and Meretseger (figure 4). Although she is never officially provided with a consort, Meretseger is sometimes shown with Ptah who, as a representative of craftsmen, was also venerated by the tomb workers. Ptah, also protector of the Valley of the Queens, was a natural companion for Meretseger, protector of the Valley of the Kings. Stelae were both stand-alone and rock-cut, the shrines themselves both man-made and natural caves.

Figure 11. Meretseger and Taweret on the stela of Hay. Turin Museum CGT 50062. Photograph by Su Bayfield.

The well-known Stela of Hay (figure 11), from Hay’s tomb number TT267 at Deir el Medina depicts Meretseger with Taweret. Meretseger stands as a woman with a cobra head. Behind her is Taweret as a hippopotamus standing on its hind legs, like a person, a characteristic way of depicting her. Both are equipped with crowns containing solar disks framed by cow horns. Each is clearly named in the hieroglyphs. Taweret rarely had any temples associated with her, and was most popular as a household deity. Although her main role was to watch over women in childbirth, she was more generally considered to ward off evil, and it is in this latter role that she was probably seen as compatible with Meretseger. Hay, who is not shown on the stela, was a foreman for 40 years, a contemporary of Paneb, and was once taken before a local court on charges of blasphemy against the king, Seti II.

The identification of Meretseger with Hathor is suggested by a number of pieces. The best indication of their association is the presenece a statue of Meretseger within the temple of Hathor. Hathor was an important at Deir el Medina and a temple was built to her at the site, the remains of which lie beneath the Ptolemaic temple dedicated to the same deity. Another example is an 18th Dynasty stela from Deir el Medina at the Museum of Turin, which shows a front-facing Hathor with a naos on her head (Turin 1658 RCGE 5732. See photograph by Su Bayfield). In the centre of the naos is an early image of Meretseger, taking a very junior role to Hathor. Hathor and Meretseger had many attributes in common and, as with many deities who shared features they were clearly seen as compatible. Hathor was the original deity associated with the peak, and they shared the title “Mistress of the West.”

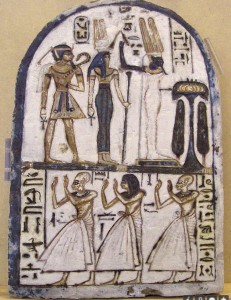

Figure 12. Meretseger with Amen-Ra and the deified Amenhotep I. Turin Cat.1451 / RCGE.5742. Photograph by Su Bayfield.

Amen-Re, Meretseger and Amenhotep I are shown together on the lovely painted stela of Parahotep from the 19th Dynasty (figure 12). In the upper registers the deities stand before the offering table. Meretseger, standing in the middle, is shown as a cobra-headed woman. In the lower register the family are shown worshiping the divine trio. This medley seems to be a collection of the deities that this family thought would best represent their interests.

Conclusion

Even though Meretseger was a guardian of the place of the dead, and there were pleas on behalf of the decesed to the goddess, the main role of Meretseger seems to have been as a judge of daily human behaviour. Meretseger was a goddess of and for the living. Many requests appear to have been apotropaic in intent, attempts to curry favour and ward off harm. In other cases matters were more serious and we find Neferabu and Amennakht seeking reprieve from punishments already inflicted upon them by the watchful goddess. She understood human frailty and, when the wrong-doer was sufficiently penitent and demonstrated an awareness of their own moral transgressions, could be compassionate, merciful and she could be reasoned with.

Although the concepts of Maat (order) and Isfet (chaos) are usually associated with royal responsibility to ensure the maintenance of balance in Egypt, the devotion to Meretseger at Deir el Medina demonstrates similar but rather less lofty concerns with dual relationships. In the penitent texts there is always the acknowledgement of right versus wrong, condemnation and forgiveness, the restoration of order to the chaos imposed by the punishment. There was also, clearly, an aspect of deferring her disapproval by offering her devotion. These expressions of personal piety provide insights into real-world concerns about personal and individual welfare and the causes for misfortune. The villagers of Deir el Medina had a clear understanding of who she was and what she could do, and they developed an intimate relationship with her, bringing her into their lives.

As the protector of the tombs of the New Kingdom kings, Meretseger ceases to be referred to after the last of the 21st Dynasty burials was interred in the Valley. As the workmen in Deir el Medina dispersed, Meretseger was abandoned.

Image credits

Many of the representations of Meretseger shown on this page are from the Museu Egizio in Turin (Italy). Some of these were sourced by Bernadino Drovetti who purchased objects from villagers in the early 1800s that he sold on. One of his best customers was King Charles Felix of Sardinia who acquired 1000s of pieces from Drovetti for his personal collection, which eventually became the basis for the Turin museum. Others in the Turin collection were obtained during the Turin Museum excavations of Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1905. At that time Schiaparelli was the director of the Turin museum and under the terms operating at that time was able to remove large numbers of excavated objects from Egypt legally.

Many, many thanks to Su Bayfield for permitting me to use her photographs. Su Bayfield owns the copyright for all the photographs for which she is credited. Her excellent website is at http://egyptsites.wordpress.com/. Many more of her lovely photographs from Turin can be seen on Flickr at http://www.flickriver.com/photos/11413503@N03/sets/72157604132418128/. Other photographs of Meretseger can be found on Lenka Peacock’s web page at: http://xy2.org/lenka/Meretseger.html.

Many thanks also to Peter Robinson for permission to use Figure 3, the shrine of Ptah and Meretseger. Peter Robinson owns the copyright for that photograph.

All photographs credited to the British Museum are Copyright of The Trustees of the British Museum and are used in compliance with the Terms and Conditions.

Photographs from the Petrie Museum of Archaeology, UCL, have been used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Bibliography

Bierbrier, M. 1982. The Tomb-Builders of the Pharaohs. American University Press.

Byrnes, A. 2012. Paneb – “The All Round Bad Guy.” Egyptological, In Brief, 13th January 2012. http://egyptological.com/2012/01/14/paneb-the-all-round-bad-guy-6901

David, R. 2002. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin.

Hornung, E. 1971 (translated by Baines, J. 1982). Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt. The One and the Many. Cornell University Press.

Lesko, B.S. 1999. The great goddesses of Egypt. University of Oklahoma Press

Lichtheim, M.1976. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume 2. University of California Press

McDowell, A.G. 1999. Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs. Oxford University Press

Meskell, M. 1999. Archaeologies of Social Life. Age, Sex, Class, Et Cetera in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell

Peacock, L. 2011. Meretseger. Images of Deir el-Medina website. http://xy2.org/lenka/Meretseger.html

Pinch, G. 2002. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Potter, D. 2012. BMEA 589- The Punishment of Neferabu. Petrie’s Sardines website. http://danpotteregypt.wordpress.com/2012/02/24/bm-ea-589-the-punishment-of-neferabu/

Reeves, N. 1996. The complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasure of Egypt’s Greatest Pharaohs. Thames and Hudson.

Romer, J. 1984. Ancient Lives. The Story of the Pharaohs’ Tombmakers. Phoenix Press

Schweitzer, A. 2007. Entre Égypte et Alsace. La collection Égyptienne du Muséum D’Histoire Naturelle de Colmar at La Collection Égyptienne de la Société Industrielle de Mulhouse. Jérôme – Do Bentzinger Editeur

Tyldesley, J. 2000. Judgment of the Pharaoh. Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt. Phoenix

Wilkinson, R.H. 2003. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson

By

By