Published in In Brief, on Egyptological, on 9th March 2014. By Andrea Byrnes.

The paintings from the tomb of Nebamun are justifiably famous for their beauty and incredible dynamism. The British Museum purchased the panels that it has in 1821 . They were located by a Greek tomb robber named Giovanni d’Athanasi, who worked as an agent for Henry Salt in Luxor. Unfortunately d’Athanasi was angered by the finder’s fee offered and he refused to give up the location of the tomb from where the panels had been removed. The location of the chapel remains unknown to this day. It was hoped that analysis of the limestone fragments adhering to the panels would be distinctive enough to give some idea of where the original site was located, but the stone was frustratingly generic and no clues were found from its composition. It is thought that it was probably located in the necropolis that lies in the region of Dra Abu el-Naga. The pieces were removed from display in 1997 for restoration. In 2009 they were returned to display in a dedicated gallery, Room 61. Other pieces from the tomb are held in other galleries including the Museum of Beaux Arts in Lyon and the Egyptian Museum in Berlin.

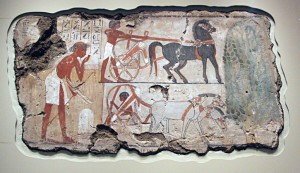

The subject matter is familiar from other chapel and funerary images – scenes of an idealized afterlife for Nebamun, his wife and children. The most famous of the scenes shows Nebamun in the marshes on a skiff surrounded by waterfowl, butterflies, with a large feline catching as many birds as each paw and jaw will permit. Various adjectives have been applied to the feline, but there is nothing soft and cuddly about it – it is an impressive collection of teeth, claws and determination. Other scenes show musicians and banquets, agricultural activities and animal husbandry, and offering scenes showing tables piled high with wonderful foods.

Very little is known about Nebamun himself. He was a scribe and grain counter at the great Temple of Amun, the ancient Egyptian version of an accountant. He was a professional man, and clearly wealthy, but he was not one of Egypt’s top elite, which makes the extraordinary quality of the paintings something of a puzzle. It has been suggested that the owners of the workshop responsible for the artwork may have been family members or great friends of the deceased, but this is speculation.

The panels themselves have a fabulous luminosity. The limestone walls of the rock-cut chapel were lined with a thick layer of dark brown Nile mud which was tempered with straw. See the last photo in the set to see this lining. This was then coated with a much thinner layer of pure white plaster and it is partly this glorious white background which, as in the tomb of Nefertari, adds to the luminosity of the chapel’s paintings.

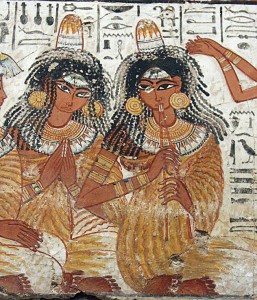

The bright immediacy of the paint led some experts to wonder if unusual pigments had been used, but analysis of the pigments used shows that they were perfectly standard. The power of the colours lies in the artist’s skillful use of the paints available. For example, each individual person is painted with dark pink skin laid solidly over the white undercoat, but the figure of Nebamun himself is painted with lighter paint stippled over the white undercoat, giving it a fabulous glow. Each of the plants, birds and animals are picked out in both strong and delicate shades, depending on the subject matter.

The draughtsmanship, the quality of each figure and each creature, is magnificent. You can believe in each scene, see it unfolding in your mind like a film. The fine handling of every detail means that individual species can be identified. For example, the goose standing on the prow of Nebamun’s boat (to the left of the feline in the above image) is the red Egyptian goose Alopochen aegyptiaca. The skill in reproducing such precise detail also means that there is something intensely personal about the expression on each face, the patterning on each individual cow, the row upon row of geese, the whiskers on the feline, the details of the hide on the folding chair, the scales and fins on the fish, the plummage of the birds, and the fine texture of the fur of the desert hares.

The composition of the paintings is the key to the remarkable appeal of these paintings and the way in which people respond to them. The artist maintained the core idea of Egyptian style and formalized themes, whilst at the same time innovating new features which would perhaps not have been possible had Nebamun been a higher status individual with greater commitment to traditional forms of expression. The dynamism of the composition is core to each segment. The hunting scene, with birds and fish filling the space, facing in different directions, is the most obvious example of this, but each of the segments is full of life. Some of the seated female musicians not only look out of the scene towards the viewer, departing completely from the usual side-view, but the strands of their hair dance and the they tilt towards each other. They are seated, but they are anything but static. In most scenes there is at least one animal, bird or person looking away from the direction of the main action – for example see the cows above where the one on the far right is looking to the right whereas the rest are all facing left. Animals, birds and more junior human members of the scenes are by and large more spontaneous and animated than the most senior human elements, but entire compositions are a feat of dynamism and expression.

Gorgeous. For more photographs from the British Museum’s Nebamun gallery, see the Nebamun photo album on our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=oa.652871851416645&type=1

By

By