By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 9. 4th December 2013

Part 1 was published on Egyptological on 18th April 2013

In part 1 I looked at how Marianne Brocklehurst acquired a collection of some 500 Ancient Egyptian objects during the three trips to Egypt that she records in her diary, cartoons, sketches and watercolours. In this section I look at the museum and the collection that Marianne and her brother Francis built for the benefit of the residents of Macclesfield in northwest England.

Building the West Park Museum

The explosion of industrialization and the conversion of open land into factories, mills and housing, created a new type of urban environment for families, with the working class often finding themselves living in very unhealthy conditions, breathing heavily polluted air. The local authorities, concerned about the unsavoury pastimes that accompanied these conditions, including drinking and cock-fighting, thought that the provision of suitable recreational areas and activities might mitigate the social issues by being suitably improving distractions. Public parks were built, providing access to an approximation of nature within which musical performances could be enjoyed, and following the 1845 Museums Act, a plethora of new museums were established. The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, which was attended by Marianne, her sister Emma and two of her brothers, gave another major boost to philanthropic donations to build and support museums outside London. Apart from anything else, the possession of museums helped industrial towns to enhance their reputations, giving them philanthropic, educational and artistic reputations to accompany their commercial legacies.

Although privately funded museums built to house personal collections were common in America at this time, they were not usual in England. Benefactors like Marianne and Peter Brocklehurst in Macclesfield and Lord Leverhulme in Port Sunlight (Merseyside), were innovators in England, eager to display their treasures, not as a matter of personal pride or to create dull repositories of objects, but in order to provide a service, to involve and educate the wider public, to improve minds and to entertain.

Although Marianne’s sister Emma Dent offered Marianne £1000.00 to house the collection at Sudeley Castle, Marianne wanted her collection to be more widely accessible. Although a copy of the Book of the Dead acquired by Marianne was kept at Sudeley Castle (now in a museum in Hanover), Marianne declined the offer, and instead made plans with her brother Peter to build a museum in Macclesfield. A Macclesfield newspaper reported how Marianne and Peter were wished to provide “educational advantages” and “inclusive recreation” (Griffiths 2004, p.228). In Marianne’s case, this typically Victorian idealism and her dismay at the deterioration of Egyptian monuments seem to sit oddly with her enthusiasm for smuggling, but it is also quite consistent with the fact that Victorian values could often be somewhat bewilderingly conflicted, frequently combining high-minded ideals with frankly questionable practises. Marianne’s feelings were clearly ambivalent. Her own collection included illegal purchases, but her diaries record her dismay at the destruction of Egyptian monuments and the emptying of tombs for the benefit of the British Museum.

Marianne first approached Macclesfield Council regarding the construction of a museum in 1894. Various disputes about the design led her to withdraw the offer, but in 1897 the proposal was revisited and all parties agreed to a final draft. In 1898 a newspaper article announced that Marianne and her brother Peter had provided £500.00 for the construction of a new museum to house her collections, together with two further payments of £50.00 each per year to cover maintenance and the services of a porter.

The West Park Museum was designed by Purdon Clarke, Deputy Director of the South Kensington Museum. It was constructed of red brick, with the initials of its founders over the door and a depiction of Queen Victoria above. The interior was formed of a short entrance vestibule, a large single gallery and a small office. The gallery was based on the Manchester Whitworth Gallery’s south gallery, and features copies of the Elgin Marbles in a frieze, just below ceiling level. As well as Egyptian and Oriental items it was to contain geological displays, art works and natural history items. The South Kensington Museum agreed to provide loan items so that some exhibits could be changed on a regular basis.

Sadly, Marianne was ill when the museum opened. Instead, the opening was presided over by her brother Francis Brocklehurst, apparently due to complications resulting from a fall in her London home, so she was unable to attend. Marianne died shortly afterwards. On her death certificate suicide is listed as the cause of death, but no other details are available. Marianne had bequeathed her collection, diary and art work to her great niece Lady Yarborough, who donated them to the museum. The museum received a staggering 15,000 visitors on its first day and Peter Brocklehurst continued to bear the ongoing costs of the museum until, many years later, he gave it into the management of the local authorities.

Photographs from 1979 show most of the museum displayed in typical Victorian-style wood-and-glass cabinets that are still found in many British museums, but today the Egyptian collection has been placed in a modern section of its own at one end of the museum, and shares the rest of the space with displays of local history and an excellent collection of Charles Tunnicliffe R.A.’s art work. The new Egyptian display, with pylon-style door frames in and out, is a self-contained area, dimly lit to preserve the lovely painted coffin, displaying a remarkable array of items in modern glass cases. The museum has been handed between different authorities and was refurbished both in 1974 and 1996. In 1998 it celebrated its centenary. It is now in the care of the Macclesfield Museums Trust.

Items in the West Park Museum Egyptology Collection

An original label created by Marianne Brocklehurst, with artefacts affixed. Photograph by Andrea Byrnes

Marianne was only interested in complete pieces, a fairly typical Victorian attitude that is clearly demonstrated in the way in which British excavations of the period were conducted, but she collected objects from many different periods, covering a variety of themes. She wrote her own labels for objects, many of which were glued to the objects themselves,, noting the limited provenances, and arranged for the coffin’s inscription to be translated by the British Museum. Since then, much more information has become available. The collection has been catalogued twice.

The first catalogue, assembled by Rosalie David at the request of the Honorary Curator Lt. Col. CDFP Brocklehurst (1980), is now out of print. It included a summarized version of Marianne’s diary entries (at a time when there was no other published version of her diary), with some of her sketches. David categorized the collection under object types in thirteen categories. The catalogue is followed by concordances and finally 31 pages of plates of black and white photographs and illustrations. The illustrations of the scarabs are particularly useful as the details are much clearer than in the photographs. The catalogue is now considered by some to be out of date, due to more recent examination and interpretation of artefacts.

A second catalogue was assembled by the Honorary Curator of the Egyptian Collection, Alan Hayward (2011a) in digital format. It is a complete catalogue of the collection containing all the known information about it. The advantages of the new catalogue, which follows the main arrangement of David’s work, are that the research is up to date, the photographs are in full colour and that the details of various objects can be updated very easily and re-issued as new information comes to light and is recorded. Alan Hayward is very active in pursuing new avenues to find out more about objects in the collection, and his findings will be incorporated into future versions of the catalogue.

As well as the items that Marianne herself assembled on her travels, Amelia Edwards and Flinders Petrie presented her with items for her collection, many dated and provenanced. Marianne and Mary were amongst the founder members of the Egypt Exploration Fund, co-founded by Amelia Edwards in 1882, and received a number items from the EEF’s excavation interests in Egypt.

The collection includes a range of objects, mainly funerary, from the Predynastic to the Roman period. Palettes and pottery from Naqada and elsewhere are the earliest objects in the collection, and there are elegant red-ware ceramics dating to the First Dynasty. There is nothing dated firmly to the Old Kingdom. The Middle Kingdom is represented mainly by jewellery from an Eleventh Dynasty tomb at Deir el-Bahri, pottery models of soul houses and scarabs, and a model boat. The New Kingdom is the best represented period, particularly by shabtis, amulets, scarabs, sepulchral cones, stone reliefs, and domestic and agricultural items. Items from the Third Intermediate Period are mainly shabtis. Late Period items include shabtis and mummified remains. A good Graeco-Roman set includes ostraca, shabtis, pottery, mummified remains, pieces of statuary and a funerary mask. There are also contemporary items of silver jewellery, mainly from Nubia, and casts of ancient Egyptian objects. Many of the items are undated, particularly items like jewellery and scarabs, and most are unprovenanced. All of the items on display are well-labelled.

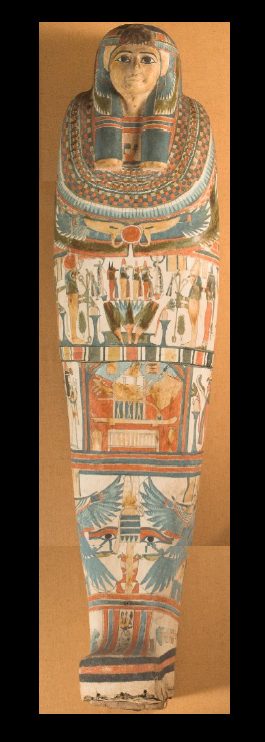

The highlight of Marianne’s collection is the anthropoid coffin, sometimes referred to as the Macclesfield Mummy (Catalogue number E16 1909.1977), in spite of the fact that the mummy itself was disposed of by Marianne and Mary after they had purchased and opened the coffin. The coffin itself is very attractive, brightly coloured and the detail is well executed, showing typical iconography and features of the Third Intermediate Period. It is unprovenanced, but the hieroglyphs identify it as the coffin of a temple singer named Sheb-Mut. Different visiting Egyptologists have suggested different dates, but its close resemblance to the C1 category in John Taylor’s Typology (2003, and in Manley and Dodson 2010) may place it in the 22nd Dynasty.

Although, like the coffin, most of the objects from Marianne’s own collection activities are unprovenanced, a number of artefacts are securely provenanced, including shabtis from two mummy caches – the Royal Cache (DB320, referred to in the Macclesfield Museum Catalogue as Cache I) and the cache of Twenty first Dynasty priests (Cache II), both found at Deir el-Bahri. See Part 1 for an account of how they were purchased. The five shabtis from the Royal Cache, acquired during the first trip, not long after discovery, are made of blue-glazed faience. Two belonged to Kha-Kheper-Re, two to Pinnedjem I and one to Maat-Ka-Re. From the Royal Cache, D38 (1846.1977) is a simple but attractive shabti decorated with features painted in black: wig and facial details, a single vertical column of hieroglyphs and a uraeus on the forehead. It belonged to Pinudjem I, the hieroglyphs reading “The illuminated, the Osiris, the King, Kha-Kheper-Re, to do all the works.” Marianne and Mary were in Luxor when Cache II was found and were able to purchase another set of shabtis during their third visit. The cache from Deir el-Bahri produced priests of Amun from the Twenty-first Dynasty. The shabtis were of a variety of types. D1 (1809.1977) is crudely formed but has been painted with standard details. Made of blue faience and painted in black, it features a seshed headband and four registers of hieroglyphs reading “The Osiris, the Fourth Prophet of Amun Ra, King of the Gods, Nesy-Amun, Justified.” Another shabti from Cache II, catalogue number D2 (1810.1977), is made of terracotta and is inscribed with the text “The Osiris, the God’s Father of Amun and Mut, Ankh-ef-en-Mut, justified”. D2, with a triangular apron indicating that it represents an overseer, was adapted somewhat ineptly from an ordinary worker shabti. The result is that it has three arms – two across the chest, as for worker shabtis, and one down the side, which indicates the status of overseer. The coffins belonging of both men are in the Cairo Museum. All of the shabtis from the Macclesfield collection have been analyzed by Glenn Janes and published with a foreword by Alan Hayward in 2010.

Deemed to be one of the most important pieces in the collection is a small and slightly damaged statuette of Tiy, Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III, who holds a lotus flower in each hand (H10 /1899.1977). 11cm tall, it is finely carved and features a well shaped torso, an elegantly engraved wig, necklaces and bracelets. Down her back is a vertical line of hieroglyphs that has been translated as “Great and favoured heiress of the sky, King’s Great Wife, Tiye, deceased.” The statuette is broken off above the knee and part of the head is missing.

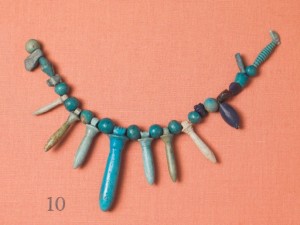

A number of pieces of jewellery (A1- A4), all attractive but none of them particularly distinctive, come from an Eleventh Dynasty tomb at Deir el-Bahri excavated by Edouard Naville in 1906 for the EEF, in the area of the funerary complex of Mentuhotep II. Other pieces of jewellery are more elaborate. A necklace of assorted beads and amulets from an unidentified Theban tomb is particularly attractive, each amulet taking a different form: a wedjat eye, images of Wepwawet and Bes, papyrus sceptres, a hand, a seal, a stamp and a cowrie shell bead (A5 / 1646.1977, shown towards the top of the article).

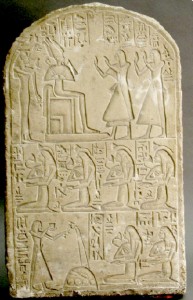

There are a small number of reliefs, of which the largest and most complex is I6 (1909.1977), measuring 51 x 35cm. Dating to the New Kingdom it consists of three registers, and is dedicated to two men, Merenptah and Maheru. Merenptah seems to be the senior of the two, shown in the top register standing ahead of Maheru, both of them offering praise to a seated Osiris and, standing behind him, Isis. Merenptah has the tile “Overseer of Horses” and Maheru was “Scribe of the Altar of the King.” In the second register four kneeling women are shown, all apparently associated with one of the men, most probably Merenptah, and include women identified as mother, sister and wife, all holding lotus flowers. The third register shows Maheru on the left facing his sister and Mistress of the House, both of whom kneel, holding flowers.

Perhaps surprisingly, because they lacked the panache of Pharaonic pieces, Marianne collected some Predynastic items, including pottery and palettes. The bird-shaped palette, G1 (1885.1977 shown at the end of this article), from the Predynastic was fairly typical of the Naqada II period, when palettes were formed in a variety of animal shapes. Made of silt-stone from the Wadi Hammamat in the Eastern Desert, part of the head is missing, and probably had an eye made of one or two different materials. One of the legs had been broken but has now been repaired. A much plainer palette, G4 (1888.1977), from the Osiris Tenemos at Abydos (possibly from Grave H26) was donated by the EEF and dates to the First Dynasty.

Pottery dates from the Predynastic, (with examples from a cemetery at Naqada), to the Ptolemaic. Most have no date or provenance assigned. All are complete examples and are very distinctive, with all the diagnostic features in tact, so they would reward study at least with a view to establishing their composition and date.

Not all of the items collected by Marianne are in the West Park Museum, and some are now in other museums. For example, she donated an ostracon to the Petrie Museum, UC32655 which is noted as “Pottery ostracon, with 5 lines of Greek, receipt of river guard tax, dated to year 30 of Augustus; given by Marianne Brocklehurst” (Petrie Museum Online Database) Two papyri are named after Marianne Brocklehurst – the hieratic funerary papyrus of Djedptahefankh, which came from the royal cache, and a copy of the Book of the Dead is now in the Kestner Museum in Hanover.

How the collection is used today

Today the museum is owned by by Cheshire East Council, managed by Macclesfield Museums Trust, and is staffed by volunteers. The Egyptian collection is under the care of Alan Hayward, Honorary Curator of the Egyptian Collection who has detailed knowledge of each of the items on display, and works with researchers to find out more about the provenance of and background to the objects in the collection. As well as continuing to provide access to Macclesfield residents to both the Egyptology and exhibits of local history and art, the staff at the West Park Museum actively encourage researchers to use the collection in their own work. The museum also continues to improve the information available about the items in Marianne’s collection, determining possible provenances, adding to knowledge about the dates of objects.

The museum has made some two useful resources available on CD-Rom: the Catalogue of Egyptian Items at West Park Museum (Hayward 2011a) mentioned above, and The MBs in Egypt (2011b) which makes available, for the first time, all of Marianne Brocklehurst’s watercolours and sketches from her three trips to Egypt. All of the entries from Marianne’s diary have also been published by Millrace Books (2004), with some of her sketches, in black and white, and her watercolours in a central colour section. Between them they make up a useful set of resources about both the experience of the MBs in Egypt and add to the bigger picture of late nineteenth century travel in Egypt.

The Education Service, operated by the Silk Heritage Trust, runs workshops based on the West Park Museum’s Egyptian collection. The ‘Egyptian Experience’ is specifically designed to involve children. Dressed in period costume, a guide in the guise of “Miss Marianne” leads children around the Egyptian collection, their activities centred on the mummy coffin and the Egyptians’ belief in the afterlife. After they have been introduced to the collection there are many other activities for children to enjoy, including object handling (using reproductions), and sketching and colouring sessions. School groups can take part in making costumes, with painted face masks, making papyri and writing in hieroglyphs.

Conclusion

The collection of Egyptian objects assembled by Marianne Brocklehurst during her three visits to Egypt, and still on display at the West Park Museum, was expanded during the years before the war with donations from Sir William Flinders Petrie, Amelia Edwards and the Egypt Exploration Fund. It is being used today to support research, to provide a resource for the residents of Macclesfield as the Brocklehurst siblings had intended, and to teach local children about Egypt’s past.

It is clear that there is much information still to be gathered about the collection, and with the assistance of other museums and specialists, who can advise about comparative material and provenance, there is much that can still be achieved.

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to Alan Hayward, Honorary Curator of the Egyptian Collection at the West Park Museum for the time taken to source various assets for the article, for answering all my questions, for checking over the finished article and for being such a knowledgeable guide to the Egyptian collection at West Park Museum.

Thanks too to Jan Picton, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, for arranging the trip to the West Park Museum.

Image Credits

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs were taken by Alan Bardsley and are copyright of Alan Bardsley and the of the Macclesfield Museums Trust, used with kind permission of the West Park Museum.

Where I have used my own photographs, permission was obtained from the West Park Museum.

Bibliography

For the full bibliography, see Part 1.

By

By