By Brian Alm. Published in Magazine Articles, Egyptological, Edition 6, 31st May 2012

Introduction

Part 1 of this series set forth the foundation principles of Egyptian religion as cosmic order (maat), duality, and divine magic (heka), which we saw expressed in tomb architecture in Part 5. Now in Part 6 we will continue our exploration of the tomb, looking for evidence of those concepts as they are expressed in art. Maat, the principle of order, is the fundamental idea upon which the Egyptian state, society, and — above all — religion rested, and that idea is stated in the static perfection and remarkable consistency of Egypt’s art from earliest times through the end of pharaonic history. In the art we see duality as mirror-image, complementary binaries in symmetrical balance. And always there is the magical power that gives the images life and permanence in Eternity.

“The role of representational art was closely interwoven with the religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians and often one cannot be understood without reference to the other,” notes Richard Wilkinson. “The single unifying theme which is invariably found in Egyptian art is its symbolic message” (R. Wilkinson 1992, p. 9). Also, as Jaromir Malek points out, “The Egyptians believed that works of art and architecture were essential to the smooth functioning of that society and, indeed, of the world itself…. The mere expression of an idea by artistic means made it efficacious and capable of functioning in its own right…. The arts were able to convey in visual form abstract concepts underlying the king’s role in society and his relationship to the gods. This process … preserved the fundamentals of the Egyptian world and the desired state of affairs for ever more” (Malek 2003, pp. 4-5).

Figure 1. Commoners crouched and waiting dutifully to be commanded: an expression of their proper role.

The deeply religious purpose of the art is evidenced by its durability over time. The magnetism of Egyptian art is by no means exclusive to those of us whose passion is Egyptian religion. Egyptian art draws people to it now just as it has for eons — “It is hard imagining a time when it didn’t exist,” as Roberta Smith said in a review of the current Dawn of Egyptian Art exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York Times, April 12, 2012). Still speaking to us over the thousands of years, it tugs, teases and baffles, and challenges us to understand its meanings.

The meanings are there but you have to look pretty closely. Take, for instance, something as simple as a footstep. A king or god steps forward decisively with his left foot but others stand with both feet planted firmly together. Or the cube-like block statues [Figure 1] of the Middle Kingdom and after, in which social status and the expectations of the Egyptian state are reflected with telling subtlety — commoners crouched in a static pose, waiting dutifully to be commanded. These are expressions of the right order of things: social, civil and cosmic.

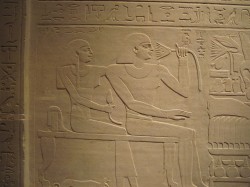

Figure 2. Thutmes III imposing order over chaos, the enemies of Egypt, on the seventh pylon at Karnak

The Battlefield Palette in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford portrays the king as a lion, mauling Asiatic enemies who are strewn about in disorder, rendered helpless by Egyptian authority. The purpose of this 31st-century B.C. work of art “was to ensure that the desired state of affairs shown on it continued in perpetuity” (Malek 2003, p. 28). It was not meant to record history but to ensure it, through magic. A half-century later, the famous Narmer Palette expressed a similar theme, and presented another canon of Egyptian art: symmetry. “The perception of completeness as a synthesis of two complementary, and sometimes confrontational, elements permeated all thinking” (Malek, p. 31). Fifteen hundred years after that, when we see the imposing Thutmes III smiting his trembling and inferior enemies on the wall of the seventh pylon at Karnak [Figure 2], or even something as idyllic as Tutankhamun spearing fish on a lazy afternoon, we are seeing the recurring theme: the omnipotent king, triumphant over disorder. (In Tutankhamun’s case, there is an additional element: it was fish that ate the 14th member of Osiris after his evil brother murdered and dismembered him, thus rendering Osiris incomplete in the worst way: the magic number was 7 and multiples thereof, 14, 42, 70 — see Part 1.) These messages are not about warfare or recreation; they’re about the ultimate responsibility of the king, as the emissary of god: to impose order over chaos.

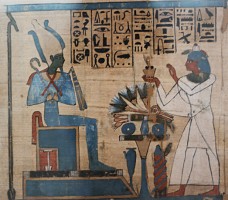

Figure 3. The throne stands on a plinth that forms the letter M, for Maat: the cosmic order that must be preserved.

The Egyptians were not always so explicit. They were especially fond of visual puns. The alphabetic sign for M, usually an owl, can also be indicated by an elongated, flat loop angled on one end; if the other end is closed, it becomes a plinth for a god to stand on or to support his throne, and the M thus incorporated stands for maat. [Figure 3] Pharaohs, too, are shown sitting on M-plinths, and resting their feet on stools decorated with “the Nine Bows” — the foreign enemies of Egypt, the Asiatics and Nubians who posed a potential threat at the northeastern and southern borders. Thus a king, charged by divine decree with the protection of Egypt and the preservation of order, tramples his enemies forever, in the graven message.

These palettes and wall scenes express in art the fundamentals of Egyptian religion: order, duality, and magic. These traditions of thought, from the mists of earliest times, continued to be expressed for three millenia, particularly — and not surprisingly — in funerary art.

The Tomb Equipped for Eternity

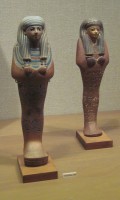

Figure 4. Small stone or wood figures called shabtis accompanied the deceased to serve them in the Afterlife.

Anything required in this life would be required in the next, so we needn’t enumerate all the grave goods that the Egyptians put in their tombs. A look at the statuettes called shabtis will suffice. The kings of the 1st Dynasty are believed to have been accompanied in death by living servants — 317 for Djer alone. Fortunately, after the 1st Dynasty the practice of human sacrifice was deemed impractical, but the need for servants remained, so these little stone figures were pressed into service as welcome substitutes. Early in the Middle Kingdom shabtis were enlisted to help commoners, too, go on with their lives — cultivating their fields, harvesting their crops, butchering livestock, fetching firewood, making furniture or bread or sandals, or whatever else life might require in the hereafter. Now that commoners had the opportunity to live eternally, they needed substitutes to pitch in and do the hard labor — otherwise Eternity wouldn’t be much fun. [Figure 4]

We can imagine that the pharaohs had more than their share of shabtis, and indeed they did. Seti I, for instance, had 700. A more traditional complement (for royalty) was 401: one for each day of the year and 36 foremen, one to supervise each group of ten. Even in spiritual matters, the Egyptians were practical — the royal household required management. But above all, it required dominance (uas), stability (djed) and order (maat), and meticulous accounting stood as testimony to those values. We saw the importance of numerical orderings in Parts 1 and 2.

By about 1000 B.C., the word shabti had changed to ushebti, “answerer” — obedient house servants answering the beck and call of their masters to bring food, drink, a game to play or whatever else they might be called upon to do. The distinction is subtle, so let’s pry into it. The population had increased, more people had risen to positions of authority and had the means to live in death as they had in life, and so there was a correspondingly greater need for house servants.

Most of the shabtis are only about six inches high, but size didn’t matter. They were stone or wood, but that didn’t matter either. Sculpting or carving something, or painting a picture of it, made it real — if words were used to give it life. Aidan Dodson notes that the word for sculptor or carver, s’ankh, means “the one who makes it living.” The images on tomb walls, too, were “active participants in the deceased’s afterlife” (Dodson/Ikram 2008, p. 77). Craftsmen recited magic formulae as they worked — for the Egyptians the spiritual was just as real as the physical. The ka in a statue was its essential reality. The physical image made the invisible visible. (See Hagen 2002, p. 100, Teeter 2011, p. 4, and Brewer/Teeter 2007, p. 189.)

Even names testify to truth realized by expression: Tutankhamun, “the living image of Amun”; Thutmes, “born of Thoth”; Amenhotep, “Amun is content, pleased”; Ramesses Meryamun, “Fashioned by Ra, Beloved of Amun”; Horemheb, “Horus is in jubilation”; Merenptah, “Beloved of Ptah”; Khenemet Amun Hatshepsut, “Conceived by Amun, Foremost of Noble Ladies,” et al. Readers of my vintage will no doubt recall Yul Brynner as Ramesses II in The Ten Commandments: “So it is written, so let it be done.” For all the Egyptological mistakes Cecil B. DeMille made in that movie, he got that part right.

Words trumped art. A person could buy a generic statue and have his own name put on it, so it could possess his ka; that it did not look like him was unimportant — all that was necessary to distinguish it was the name (ren; see “aspects of being” in Part 4). Likewise, kings replaced previous kings’ names on statues with their own, and in the process, accrued their predecessors’ divinity. And by claiming the achievements of others as their own, kings of lesser merit could bask in the reflected glory, now made fact by the written word.

Artistic Representation: Methods of Portraying (and Creating) Reality

Figure 5. A 12th Dynasty offering bearer carries a basket of food to sustain her master in the Afterlife.

Grave goods didn’t have to be “real” as we regard reality. Paintings, models or sculpted objects were made real by the magic of ritual declaration — di ankh, “given life.” There was a close connection between words and art; both could create reality. As mentioned in Part 1, images of people in tombs show them in perfect shape — men strong, vigorous and in their prime, women radiating youthful grace and beauty — and this image becomes their reality for all Eternity: what is shown in art or written in words is real and will never change. “Egyptian art was essentially functional, in that funerary paintings and sculpture, for instance, were concerned primarily with the continuance of life — the works of art were intended not merely to imitate or reflect reality but to confirm and perpetuate it.” The purpose was “to represent, influence and manipulate the real world … Egyptian art was concerned above all with ensuring the continuity of the universe, the gods, the king and the people” (Shaw/Nicholson 2008, p. 41).

It was nonetheless practical: in the 12th Dynasty tomb of chief steward Meketra, for instance, a woman carries a basket full of beef, bread and vegetables so that Meketra will be assured of a balanced diet in the Afterlife. [Figure 5] Another grave item from the 12th Dynasty — the turquoise collar of storehouse manager Uah — may dazzle the casual visitor to the Metropolitan Museum who passes by, unaware of its subtle but significant testimony to faith: Hathor, the daughter of Ra, wife of Horus (her name literally means “the mansion of Horus”), divine mother of kings, and the “Lady of the West” who waited each evening to receive the setting sun, was also revered as the “Lady of Turquoise.” [Figure 6] Hand mirrors typically had umbrels formed in the image of Hathor, who was also the goddess of beauty and feminine grace, and they reflected, if you will, a meaning that would be explicit to the Egyptians but opaque to others unless they knew that the word for mirror was also the word for life, ankh; look in the mirror and you see the living image of yourself, beautified by the divine intercession of Hathor. [Figure 7] Theology was everywhere, in everything.

Now, here is an irony. The religion was not dogmatic; there was no rigid canon of belief. But there certainly was a canon of art. The basis of art was religious, and “severe deviation from the norm might have endangered the potency and efficacy” of the art, as Malek notes, so the early standards were maintained for 3,000 years — not as fossils of the earliest times, but as continuing expressions of living truth. The religious beliefs that “mitigated against radical innovation ensured that artistic conventions, such as the method of representing human figures and their relative sizes, the way three-dimensional objects were translated into two-dimensional depictions and the emphasis on symmetry, once established, remained standard for the rest of Egyptian history” (Malek 2003, pp. 7-8).

That is not to say there were no differences — there were, at times of estrangement between the Two Lands; in the 12th Dynasty, for example, when a trend toward more naturalism replaced the traditional idealism in portraying human figures, and most noticeably in the short-lived Amarna Period, when the heretical 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten forced the only extreme departure from the canon. Just as with political stability, there were lapses, but over a period of 3,000 years the consistency was remarkable, and still unique in the history of artistic representation.

Let’s look at those enduring conventions: dimensional renderings, the human figure, and symmetry. With symmetry, we are on familiar ground — duality, balance and harmony. In [Figure 8], the symmetry of Ramesses II’s mirror-image cartouches, Ra-Harakhty doubled and standing on the glyph nebu (gold, the flesh of the gods), the djed (stability) pillars and the uas (dominion) staffs — all flanking the ankh — all express order. But as for dimensional perspective and figures, we struggle. This Egyptian art doesn’t look like anything else anywhere, at any time. What could they have been thinking? Whatever it was, they did it about the same way for thousands of years, so there must have been some rationale behind it all. Indeed there was.

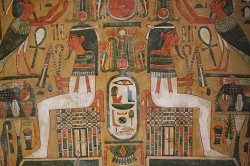

Figure 8. Symmetry testifies to order: mirror-image cartouches, Ra-Harakhty deities, djed pillars and uas staffs.

The Egyptian artist’s goal was to convey information about things instead of presenting them three-dimensionally: he didn’t try to make it “look like” reality, he recreated reality. It’s an important distinction, and fundamental to understanding the “strangeness” of Egyptian art. If a box is square, we would try to show its three dimensions by turning it into a trapezoid, foreshortened to show depth. The Egyptian artist would say it is not a trapezoid, so don’t make it look like one: it’s a square, so it must be shown as a square. If the box has things in it that are important to see, we would tip it so the viewer could look inside. The Egyptian artist would show those things above the box and positioned so the viewer could see as much information as possible, at once and without distortion. If each object is best understood from a different angle, that’s how it’s positioned; some frontally, others from overhead. The picture of the 18th Dynasty garden pond of Nebamun illustrates the point: both frontal and aerial views simultaneously present all the information. [Figure 9] Things farther away looked higher to them, not smaller, so in order to show perspective they stacked objects horizontally, putting distant objects above closer ones, instead of diminishing their size, as in Western art. What we call reality, they would call incomplete, distorted information.

Figure 9. In Egyptian perspective, both frontal and aerial views seen simultaneously present all information at once.

How do we understand this? Emily Teeter offers an excellent explanation in Egypt and the Egyptians: the art of Greek, Roman and other Western traditions is perceptual; Egyptian art was conceptual. Perceptual art is focused on the subject from the perspective of the observer and uses foreshortening to create the illusion of three dimensions. That’s what we’re used to, so Egyptian art looks strange. Conceptual art portrays the subject from its own perspective, because the purpose is to convey all the essential information about the object itself, not how it appears to the viewer, and do so all at once. If the top and the side of an object are both important, they are shown simultaneously (Brewer/Teeter 2007, pp. 194-204).

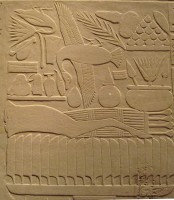

Figure 10. Parts or progressions of a story may be conveyed in several scenes in different registers, like comic strips.

Sometimes the whole story cannot be told in one picture. Parts or progressions of a story may be conveyed in several scenes in different registers (horizontal panels, like comic strips). [Figure 10]. The same person may appear in successive scenes with different gods or engaged in different activities. Serial events may be recorded on one plane, or in adjacent registers. Even the repetitions themselves may express a message or make it more emphatic, just as in the written language, where doubling a glyph could express duality and tripling it, plurality, or adding a superfluous phoneme (the phonetic complement).

No doubt the oddity of Egyptian art that most people think of first is the human figure. The torso and one eye are seen from the front, but the arms, legs and face are seen in profile. Yet we see the arches of both feet, so a figure walking to the left presents two right feet — because the arch is the most notable feature of a foot and therefore conveys the key fact about the idea “foot.” [Figure 3]

Status and role were expressed by artistic conventions such as size, color, pose and placement. Pharaohs are larger than other people, but smaller or the same size as the gods. Estate owners are bigger than their subordinates. Men are shown ruddy red and women pale, telling us that men work outside and women inside. That was not reality — noblewomen went outdoors, too, and most commoners were out and about every day, shopping and managing the household dealings — but the idea of gender roles was the information the Egyptian artists wanted to convey. Pharaohs and gods are posed with the left foot forward, active and assertive. Children are shown holding one finger to their mouth. Women in mourning are shown with their hands raised, throwing dust over their heads. Scribes are shown sitting with knees spread apart to pull their kilt tight, to use as a desk. A man’s wife always has her arm around her husband’s shoulder or waist, or is touching him as he stands or sits in front of her. You can tell a god from a mortal at a glance: mortals have straight beards, and gods (or deceased and therefore fully deified pharaohs) have curved beards — with one exception, Ptah, who always has a straight beard but you can identify him anyway because he’s always mummiform, wrapped up tight, wearing a skull cap, and usually clutching a uas/ankh/djed staff.

Again, the purpose of Egyptian art was to convey as much information as possible or reiterate a myth, at once and in formulaic ways consistent with canonical practice, without creative deviation — for religious ends. Artists in Egypt were considered craftsmen, not free-spirited innovators, and they were expected to deliver consistency — hence the grid system.

Figure 11. The grid system used an 18-square standard to represent the human body consistently (14 for sitting figures).

A wall to be painted was first coated with plaster and then a grid of 18 squares was snapped on it with a string dipped in red ink, or drawn with a straightedge. Each square was about equal to the width of a closed fist. Parts of the body were measured in multiples of the grid square: the knee at the 6th square up, the bottom of the hip at the 9th, the neck at the 16th. The 18th was the hairline, not the crown of the head, to allow for headdresses and crowns. [See Figures 3 and 11.] This 18-grid system (14 for sitting figures) was in place by the 5th Dynasty (24th century B.C.) and it remained standard until the late Third Intermediate Period (1069-664), when the proportions changed to a 21-square grid, which made the royal figures taller and thinner. (That’s why the Ptolemys, later on, look so different. Given the facts of Ptolemaic rule, I venture to say that the intent was to proclaim their greatness in lieu of reality.) Once all that gridwork was done, a draftsman made a sketch in red ink, after which a master draftsman made corrections in black. The process was so well organized that several men could work on the same scene, doing different parts of the process at once, like an assembly line. (For detail on the grid system, see Robins 2008, p. 107, and Brewer-Teeter 2007, pp. 199-201.)

For relief sculptures, it was largely a matter of lighting and surface material. Inside tombs, raised relief was used; the walls were usually prepared with a layer of plaster, about an inch thick, so it was easy to sculpt, but moreover, raised relief captured the available light from torches made of twisted fiber or from oil lamps. The incised method, sunk relief, was typically used on external surfaces, to make the best use of sunlight.

Art and Its Meanings

Egyptian art spells it out for you, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Meanings can be imbedded in layers of imagery, expressed cryptologically and reiterated in different ways. You do have to know what to look for. “Works of art were intended to be ‘read’ like an elaborate code,” say Shaw and Nicholson (2008, p. 41), so let’s do that. We can barely scratch the surface here, but there are some excellent books to help carry the matter forward for those who wish to dig deeper; I’ve referenced some of my favorites at the end.

Figure 12. A feast of information, full of mythological references and religious meanings, can be extracted from a cryptogram.

It’s easy to spend an hour finding all the pieces in a picture, all of which interact with each other, repeating the message or adding more to the story. [Figure 3] is a brief but telling example: Osiris with his atef crown, heka crook and nekhekh flail, whose throne, on top of an M-plinth, incorporates both the H-glyph for “Horus” and the sema (union) symbol (sema-tawy, the Union of the Two Lands), under protection of the sky, pet, plus the staff of dominion (uas) — and that’s before we even get to the writing on the wall. [Figure 12] is a veritable feast of imagery: a symmetrical scene with two Osirian figures (note the curved beards) sitting on serekh-like thrones on top of Maat-plinths, with crooks and flails, offering tables laden with food, and two Bas above, all centered around a cartouche of Osiris (Usira, Wennefer “The Eternally Good One”), under the sky, pet, itself surmounted by Ra and the double uadjet cobras (uraei); and the cartouche is resting on a combination of the neb glyph (lord) and the word nebu (gold): “The House of Gold,” the burial chamber — hence Osiris, Lord of the Dead.

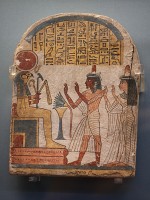

Figure 13. Husband and wife are sustained in Eternity with the offerings of good provided to them through the king’s grace

“Objects, people or even gestures may be represented so as to suggest the form of hieroglyphic signs and thus spell out a symbolic message” (R. Wilkinson 1992, p. 11). In Figure 11, for example, the two people raise their arms in adoration, forming the determinative for the glyphs dua (adore) and iau (praise) — expressions of subservience to a god or king. [Figure 11] Headdresses may spell out the deity’s name: Isis, for example, has an iset throne on her head; her sister Nephthys (Nebthet), the “Lady of the Mansion,” wears the neb + t (the t feminine ending converts neb from “lord” to “lady” or “mistress”) and the het (hat, hut), “mansion” glyph found also on thrones.

Figure 14. The food on the offering table, blessed by the words of institution and written in stone, will last forever

The phrase hetep di nesu, “an offering that the king gives,” was a formulaic prayer asking for food offerings to be brought to the ka of the deceased, who is often shown next to an offering table with food piled on it — so presumably the inscription on the outside of the tomb, addressed to passersby, was effective. We’ve seen that sort of presumption before: the Book of the Dead always recorded, preemptively, a happy ending to the judgment of the soul. [Figure 13] Invoking the king indicates that it was necessary for him to intercede, which “illustrates the essential role played by the king as divine intermediary at the heart of each individual’s funerary cult” (Shaw/Nicholson 2008, pp. 232-33). The food on the table, thus blessed by the words of institution and written in stone, will last forever. [Figure 14] The offering table itself, reduced to a simple plate with a loaf of bread on top, becomes the glyph R4, hotep, or hetep, “offering,” and in another context “pleased,” “content” or “satisfied,” as in names such as Amenhotep.

Figure 15. Hatshepsut, the 18th Dynasty female king, presents nw jars filled with wine, milk or water, as an offering to a god.

The magical formula hetep di nesu “underpinned the whole posthumous survival of the deceased” (Dodson/Ikram 2008, p. 86) and reminded everyone that ultimately all offerings were from the king. That makes practical sense, since the king technically owned all the land and the produce thereof, but also religious sense in light of the king’s pivotal responsibility to preserve the order of the universe. For the people of Egypt, life itself was, in reality, an offering that the king gives. For the gods, the offering was more likely to come in the form of nw (nu) jars filled with wine, water or milk, or as perfume from a lotus, presented to them by the king. In this state in which order was paramount and institutionalized by social structure, everyone was subservient to someone higher up. [Figures 15 and 3]

We see many examples of the lotus (seshen) turned toward a person or a god — gods and goddesses were moved even more by perfume than by music. [See Figures 3, 11, 13] “Enjoyment came above all through the nose, so much so that a nose hieroglyph was used in every word meaning ‘pleasure’” (Hagen 2002, p. 129). But it went far beyond pleasure: all this olfactory imagery was really about rebirth. The Egyptians received the breath of life through the nose, as you see depicted often in art, as a deity extends an ankh toward someone’s nose. The god of perfume, Nefertem (son of Ptah and Sekhmet), is shown with a lotus blossom on his head. Let’s not forget that the lotus was a symbol of the Creation, because in myth the sun god Ra was born from the lotus when it sprang up on the Primeval Mound; and because the lotus closes at night, sinks beneath the water as if returning to the primordial ocean of Nun, and reopens in the morning, it is also a symbol of resurrection. The word mes, incidentally, is used for both “bouquet” and “birth” (Dodson/Ikram 2008, p. 121). Another interesting double entendre is senetjer, which meant both “incense” and “to make divine” (Robins 2001, p. 7).

Mortals, too, seem to have been overcome by aromas. When Hatshepsut wanted to legitimize her divine birth, she explained that Amun had come to her mother, Ahmose, assuming the form of her father, Thutmes I, and captivated her with his divine fragrance. Amun told the queen that she would bear him a daughter and that she should name her Khenem-et-Amun Hatshepsut, “She Whom Amun Embraces, Foremost of Noble Women.” On a more casual plane, note the ointment cones that adorned the heads of guests at a dinner party — a perfumed glob of animal fat that melted during the course of the evening, streaking their heads and shoulders and filling the air with sweet scent. Whenever I’ve mentioned that in lectures, people have groaned in disgust. But we have to adjust our senses to Egyptian times, and recognize that ultimately everything resolves to a religious basis.

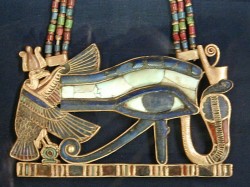

Figure 16. The Eye of Horus signified “whole,” “well being,” and so it was a popular protective amulet, but it also represented Ra.

And finally, vision. The Eye of Horus was called uadjat (a.k.a. wedjat), which also means “whole,” and therefore “well being” or “perfect,” and so it was a popular protective amulet, and on coffins it provided a magical means for the deceased to look out. Less than a whole is a fraction, and so the Egyptian mathematicians indicated fractions with the components of that eye image. In Figure 16, we also see the Two Ladies (Nebty): Nekhbet, the vulture goddess wearing the atef/hedjet (white crown) of Upper Egypt and perched on a shen ring, and Uadjet, the cobra goddess wearing the deshret (red crown) of Lower Egypt. [Figure 16] This is the right eye of Horus, representing the sun (Ra); his left eye was the moon (Thoth). Again we are reminded of the Egyptians’ concepts of magic and duality, as well as their practical applications of myth and the entire religious milieu that informed life and death.

Conclusion

Roberta Smith commented in her review of the current exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum: “In many ways the art of dynastic Egypt brought nature to a standstill, freezing the figure in an elegant, quietly pulsing suspended animation. Especially in its grandest, most monumental expression — the eerie, somnolent statues of the gods and the pharaohs who were their earthly junior-god emissaries — Egypt offers us the sleekest, longest-running style in the history of art. It is also probably as instantly recognizable and firmly imprinted on human consciousness as any we know.”

Perhaps that’s why we love it so — enough to try to understand it, yet challenged by its secrets and awed by its timelessness. We, the children of the future, reach back in time like kids on a carousel, striving to grab the brass ring that passes by just beyond our grasp. Our urge to know, our “brass ring,” is like the shen circle in Nekhbet’s clutches: endless. With each attempt we come closer, but a gap still remains, and it is filled with enduring wonder.

This series was originally planned for five parts, but the subject refused to be contained in that frame. We will conclude it next time with a historical perspective, returning to the formative roots of Egypt’s religious and socioeconomic culture, and also note the only major departure from the ancient heritage — the 18th Dynasty heresy of Akhenaten — to see what we might learn from that.

References

Brewer, Douglas J, Emily Teeter. 2007, Egypt and the Egyptians, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge

Dodson, Aidan; Salima Ikram. 2008, The Tomb in Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

Hagen, Rose-Marie and Rainer. 2002, Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs, Taschen, Cologne

Malek, Jaromir. 2003, Egypt: 4000 Years of Art, Phaidon, London

Robins, Gay. 2008, Art of Ancient Egypt, Harvard U.P., Cambridge, Mass.

Robins, Gay. 2001, Egyptian Statues, Shire, Princes Risborough, U.K.

Shaw, Ian; Paul Nicholson. 2008, Illustrated Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, American University in Cairo Press

Smith, Roberta. “Such Magnificent Beasts the Egyptians Made” (The Dawn of Egyptian Art exhbit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), in The New York Times, April 12, 2012

Teeter, Emily. 2011, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge

Wilkinson, Richard H. 1992, Reading Egyptian Art, Thames & Hudson, London

Wilkinson, Toby. 2008, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

Image Credits

Figures 3, 9, 10, 11 and 12 – photographs by Andrea Byrnes

Figure 16 – photograph by Jon Bodsworth

All other figures – photographs by Brian Alm.

By

By