By Barbara O’Neill. Published on Magazine Articles on Egyptological. April 3rd 2012.

Each day is a little life, every waking and rising a little birth, every fresh morning a little youth, every going to sleep a little death.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Introduction

A recent exhibition on East African headrests indicates that their use may range from a symbolic function in marking the significant transition from youth to adulthood, to the more practical function of protecting elaborate hairstyles during sleep which remains a factor in the use of headrests in some African tribes today (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; ‘Triumph, protection and dreams: The East African headrest in context’). Headrests have an iconographical status throughout the African continent and are a recognisable feature of ancient Egyptian culture. The act of sleeping itself is the subject of myth, ritual and superstition interwoven within the religion which permeated all aspects of this complex civilization. Headrests, sleep and dreams are interrelated within Egyptian ideology. Was the Egyptian headrest a symbolic object; a funerary essential; an everyday domestic object or an item which fits all of those descriptions? In the following article I will explore aspects of sleep in ancient Egypt, from the headrests used in the act of sleeping, to complex meaning surrounding dreams.

Headrests for the living and for the dead

The oldest ancient Egyptian headrest extant today dates to the Third Dynasty BC. The use and symbolism of the headrest may however predate the Dynastic era by many hundreds of years. Alain Anselin’s work on ancient Egyptian and contemporary African pastoral peoples, suggests that the ‘Egyptian’ headrest belongs to a much older tradition amongst Saharo-Nubian peoples in the ‘African hinterland’ of Ancient Egypt during the Predynastic period’ (Anselin, 2011). Figure 1.

In his study of Afro-Egyptian cross-cultural influences, Anselin highlights headrests and the wAs-sceptre as objects shared by “Predynastic civilisation, the Ancient Egyptian civilisation itself, and contemporary North East African shepherds” (Anselin, 2011). Other commonalities include aspects of language, possibly resulting from complex Saharan-Nubian influences on early Egyptian culture.

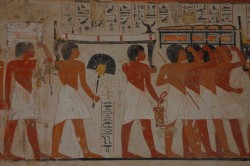

By the Old Kingdom, the use of headrests in the Egyptian funerary programme is well established, as evidenced by their frequent depiction in elite tomb art. An unusual early example of the headrest as an item of funerary goods was discovered packed within the outer wrappings of a Gebelein mummy. Now in Turin and described in the literature rather starkly as ‘the bundle’ (Egyptian Museum, Torino, Italy; CGT 13020) this adult mummy, which dates somewhere between the Third and the Fourth Dynasty BC (2686-2450 BC) is wrapped in a foetal position with a full sized wooden headrest tucked discreetly near the lower extremities. This Old Kingdom example suggests that the headrest was already singled out for use in the afterlife from an early period. The Gebelein mummy ‘bundle’ contains an intact body and no other grave goods. Figure 2.

Supporting evidence that headrests were also used in life can be found in artefacts dated to the Middle and New Kingdom phases, recovered from domestic settlements at Lahun, Deir el Medina and Tell el Daba’a. In many of their designs, the headrest’s function in supporting a sleeper’s head is emphasised through stylised hands which appear to cradle the head. Figure 3.

Headrests found amongst an abundance of grave goods discovered in the intact Eighteenth Dynasty burial of Deir el Median architect Kha, support the evidence that headrests were not exclusively funerary but probably used as ‘pillows’ on the bed. Kha’s headrests show signs of wear with traces of fibres and fabric remaining on the headrests, indicating that they were once padded with cushioning materials. There are smaller amuletic examples of headrests in the display cases of most Egyptological collections; often recovered from within mummy wrappings. Figure 4.

The dimensions of headrests recovered from burials closely match those with a ‘domestic’ provenance. It appears to be the case that at least some household headrests may have found a secondary use upon the death of an owner in a similar way to that in which other domestic articles, including mirrors, eye-paint receptacles and other household vessels found their way into the tomb. Some headrests bear an owner’s name alongside funerary epithets including mAa-xrw ‘true of voice, justified’ and ‘repeating life’, terms reserved exclusively for the deceased. Headrests have been found amongst the tomb goods of men and women, the poor, the elite and royalty. Figure 5.

For the living, headrests had a practical function, raising the head slightly, keeping it cool, offering some protection from crawling, biting or stinging insects. The padded headrest once owned by Kha, would have been ideal in supporting his head gently on a hot summer’s night in Thebes. Although most domestic headrests were functional, usually wooden and plain, others bear elaborate decoration incorporating inscribed spells aimed at protecting the sick, pregnant women or to guard against illness and disturbing dreams. Their amuletic protection would have functioned magically as one slept.

An assembly of domestic gods and goddesses are associated with headrests found in both funerary and domestic settings. Deities associated with these artefacts include Bes, Beset, Sobek and Tawaret, gods and goddesses most often associated with women, children and the vulnerable sick. Often brandishing knives and writhing snakes, these deities provided ritually charged protection against a multitude of threats. Figure 6.

Other composite creatures appear alongside magical texts on headrests recovered from Middle Kingdom Lahun, the Twelfth Dynasty pyramid town which served the pyramid-cult of Senwosret II, and from New Kingdom Deir el Medina; the latter home to the craftsmen of the Royal Tombs in the Valley of the Kings. These fearsome beings were harmless to innocent sleepers and regarded as potent protection against bad dreams and ill-intended nocturnal spirits, intent on creating havoc for the living. It seems that headrests were valued possessions which functioned in life and in death.

Keeping your head in the afterlife!

A less pragmatic, cultic rationale influenced the function of headrests as ‘a pillow for eternal sleep’. In this context, the headrest functioned symbolically; its presence ensured that the head remained physically intact with the body in the afterlife. Losing one’s head after death appears to have been almost as terrifying a prospect for an ancient Egyptian as losing one’s head in life. Preservation of the head was crucial for the deceased; it was central to the ability to speak, to breath, to see and to hear and essential in surviving the trials involved en route to the netherworld. Ultimately, success in the final judgment of the dead was paramount. Failure to keep one’s head might result in a catastrophic second death resulting in the annihilation of the body and its kA, the soul-like entity which enabled the deceased to receive sustenance in the form of prayers, libations and food offerings.

The importance of preserving the head can be seen in the creation of dummy or reserve heads in Old Kingdom elite burials, a focus later echoed in the Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts. These texts evolved out of the Pyramid Texts and developed during the decentralised and transitional period of the First Intermediate era (2181-2025 BC). At this time spells and related imagery, once placed on the walls of royal tombs, became available to the non-royal elite who included Coffin Texts on the outer and inner surfaces of their wooden coffins in the early Middle Kingdom (2025-1700 BC). These texts, which functioned as ritually protective spells and instructions, were intended to ensure safe passage to the afterlife; a journey fraught with danger for the deceased. The Coffin Texts were inscribed in ink, often accompanied by object friezes which featured a range of ritual items essential to the afterlife. These object friezes often include multiple headrests.

There is a Coffin Text for each and every part of the body, ensuring preservation and full restitution of function from the head, right down to individual toenails. The limbs, the skin and even extending to the ephemeral, other worldly aspects of the body, including the bA, the kA and the mysterious shadow; all corporal and spiritual elements are protected by specific spells. Aside from headrests, associated object friezes depict a range of other objects associated with the head, including sacred oils; bags of blue and green eye make-up; kohl pots and cosmetic containers; all represented close to the head-end, inside the coffin. At the foot-end of the coffin, texts related to walking and movement are placed alongside images of sandals, cased mirrors, boxes containing fine linens, staffs, sticks and weaponry.

The Coffin Texts are replete with chthonic, demon-like creatures, menacing towards the unwary and the unworthy alike. These magical spells emphasise that, at least for a transitional period in the journey towards eternal life, the deceased required full use of the physical body; intact, alert and able to communicate with creatures who could assist or block one’s ultimate transition to the heavens. In order to succeed in such trials, one needed quite literally, to keep one’s head! Unsurprisingly, the head is often mentioned specifically in the context of keeping it in place, keeping it upright, allowing it to be raised and to function fully in death:

‘Hail to you, you mistress of brow and neck. May you place for me my head upon my neck when you gather together life for my throat. My head will not be cut off, my neck will not be severed, my name will not be unknown.’ Coffin Text (CT) 229

‘Oh lift up your head, says Re. Detest sleep, hate inertness, be far from them as Horus, that you may live.’ CT 69

‘Oh sleeper, turn about in this place which you do not know, but I know it. Come that we may raise his head. Come that we may reassemble his bones.’ CT 74

Later funerary texts, known collectively as the ‘Book of the Dead’ (a modern term encompassing around two hundred funerary compositions known to the Egyptians as the ‘Book of Going Forth by Day’) included a spell to be inscribed on either a full size or amuletic headrest which would prevent the deceased from having his head removed from his body. The sense of anathema, already established in the Coffin Texts, regarding the punishment of ‘walking upside down’ is continued in these later texts. Fire-spitting monsters appear with the sole function of destroying the heads, and therefore any hopes of an afterlife, for those doomed to walk upside down for eternity, as if the latter affliction wasn’t bad enough! Lurid details of exactly what constituted these watery depths is gruesomely detailed in all of the funerary texts.

As coffin design evolved, it was not practical to place headrests inside the coffin. Smaller amuletic headrests, referred to earlier, become more common in the New Kingdom, wrapped inside the mummy bandages, or placed with other amuletic tokens inside the burial chamber. As evidenced in the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Kha, household and funerary headrests continued to be placed in tombs throughout the New Kingdom.

The Solar Connection

By the New Kingdom, and possibly even earlier, headrests were closely associated with solar imagery; the head, like the sun, was lowered in the evening to rise again in the morning. Layers of meaning related to regeneration and rebirth associated with solar theology, was applied to the headrest from this era onwards. Iconography related to Shu, the god of the air who supported the sky, often appears on New Kingdom headrests. Shu was associated with the rising and the setting sun and with the ability to breath in many passages from the Book of the Dead.

By the Nineteenth Dynasty, the headrest hieroglyph or ‘weres’ symbol (Gardiner Q4) is associated with other protective amuletic symbols including the Osirian djed pillar, (Gardiner R11), the ‘Isis knot (Gardiner V39) and the heart amulet Gardiner F34. All four are represented in lists of ritual objects depicted in a copy of the Book of the Dead which belonged to the scribe Ani. Like the djed symbol and the ankh sign, the headrest symbol was often incorporated into an anthropomorphic form within Book of the Dead vignettes. Other New Kingdom depictions show the headrest as a solar barque; a highly stylised example can found in the Papyrus of Anhai, which dates from the Twentieth Dynasty.

Hydrocephali, small inscribed disks of papyri, metal or leather containing protective spells related to renewal and rebirth, were placed under the head of the deceased from the later phase of the New Kingdom into the Late Period. Most were decorated with extracts and vignettes from Chapter 162 of the Book of the Dead related to creating heat under the head of a transformed spirit or an akh, a desired state for all the deceased. Like the headrest, the hydocephali offered protection for the head of the deceased. Most examples date to the Late Period, although these amuletic disks may have had earlier origins.

As night falls

Scenes of Hathoric dancers in the tomb of Khereuf, chief steward to Queen Tiye at Thebes, suggest that night time was not only the period when the dead would sleep, but was fraught with dangers which could be dispelled through song, dance and religious ritual. Texts accompanying the images of dancers in Khereuf’s tomb refer to some of these nocturnal rites which replenished the deceased; ‘Come rise, come that I may make jubilation at twilight and music in the evening! Oh Hathor, you have been exalted in the hair of Re, for to you has been given the sky, deep night and the stars’.

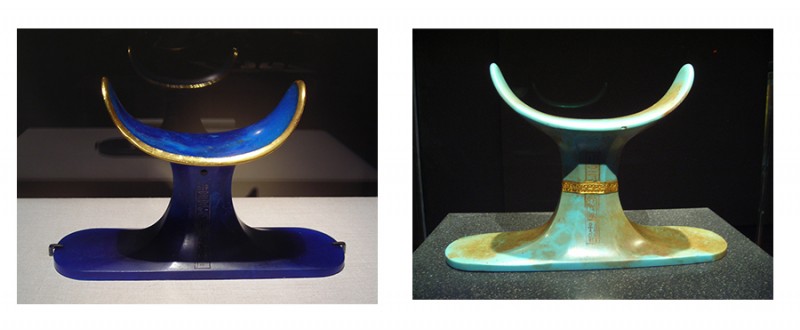

Night, in the funerary programme, was a period of vigils and of cultic rituals which featured torch-lit processions and incense-burning ceremonies intended to mark the passage of the deceased through the netherworld. The solar barque (the mythical boat on which the sun god Ra traversed the skies by day and the underworld by night) ensured that the deceased, like the sun god, would arrive safely in ‘the west’ the land of the dead, at dawn. This close association between the headrest and the solar barque may indicate why this item was such a favoured addition amongst grave goods throughout the Pharaonic period (Figure 7).

And so, to sleep, perchance to dream

If the tomb represented the home for the deceased, the burial chamber represented the bedroom. Some of the earliest instructions in Egyptian literature refer to the important parallel tasks of founding a house and preparing one’s tomb. This connection between house and tomb may be the reason for the popularity of domestic items, much favoured as tomb goods throughout the Pharaonic era. Apart from headrests, beds and linens, an array of other items associated with evening toilette, are found amongst tomb goods or represented in offering scenes. Figure 8. Closely related to this concept of the tomb as a dwelling is the idea that the deceased ‘lived’ there, or at the very least, the physical body ‘slept’ there. The texts on a headrest which belonged to Qenherkhepesh, a scribe from Deir el Medina reads,

‘The scribe of Thoth and of Ma’at who love him, Qen-her-khepesh-ef son of Pa-nakhte, justified. Spell for a good sleep in the land of Amen, by the royal scribe Qen-her-khepesh-ef, justified. A good sleep inside the western district for the justified. Made by the royal scribe Qen-her-khepesh-ef, justified.’ (McDowell, 1999).

Whether this scribe had made his own headrest is not known. The term ‘justified’ referred exclusively to someone already deceased. Practicalities (and perhaps, superstition) may indicate that Qenherkhepesh’s son, or a close male relative would have completed the inscription on the scribe’s behalf. The idea that the dead were sleeping, or that they occupied another dimension not totally disconnected from the living, is indicated in letters to the dead written on papyrus and ostraca, often penned by, or for, the villagers at settlement sites including Lahun and Deir el Medina. Letters to the dead provide a fascinating testament to how the memory or influence of the deceased was maintained amongst the living in a community, often for a significant period after the funeral. There was a perception that the deceased could intervene in problems affecting the living and difficulties in life were often suspected of having been instigated by wayward spirits in the netherworld. Figure 9.

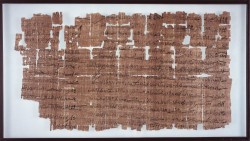

Dreams were not taken lightly in ancient Egypt. The state of sleep was understood as perfectly suited for communication with the gods, or with the dead. In the Middle Kingdom ‘Instruction of King Amenemhet I’, the elderly monarch appears in a dream to his son, Senwosret I, in order to warn him of the perils of assassination; and he should know, as this was the fate suffered by Amenemhet himself. A copy of the dream book owned by the same Qenherkhepesh who left us his inscribed headrest, is the earliest example of this genre known. Qenhekhepesh’s dream book is dated to Ramesside Deir el Medina, (Papyrus Chester Beatty III); although the dream-book genre is believed to have had earlier, Middle Kingdom origins. Figure 10.

Qenherkhepshef’s papyrus contains intriguing responses to a wide range of dreamed situations, and was used as an interpretative guide as to whether a dream was ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Magical overtones permeate dream interpretations, hardly surprisingly, as most domestic ills, from sick cattle to bad dreams, were perceived as ‘treatable’ with a quirky blend of ‘the practical and the subjective’ (Allen, 2005). Science, as a discrete discipline, did not exist in ancient Egypt and disturbing or puzzling dreams were understood to have supernatural origins and were treated accordingly with a blend of the pragmatic and the supernatural. Certain dreams were seen as ‘a revelation of truth’ (Quirke, 1992). There was no concept in ancient Egypt, that such matters might involve the ‘dark arts’. Magic or ‘heqa’ was a part of everyday life, as natural to the Egyptian peasant or nobleman as eating or breathing ‘Magicians were not calling upon an alternate and deviant theology, but were participating in the realm of established religious practices’ (Teeter, 2011).

Qenherkhepesh’s dream book was a family affair; penned by his grandson, the scribe Amen-nakht, who was the son of Kha-em-nun, Qenherkhepesh’s oldest child. The texts allow insight, not only into the dreams of these ancient people, but into the everyday experiences of their lived lives. The dream book is divided into lists of auspicious and inauspicious dreams:

Auspicious dreams:

‘If a man sees himself eating crocodile meat: good, it means becoming an official among his people.

If a man sees himself burying an old man: good, it means prosperity.

If a man sees himself sawing wood: good, it means his enemies are dead.

If a man sees himself seeing the moon shining: good, it means a pardon from god.

If a man sees himself in a dream slaying a hippopotamus: good, a large meal from the Palace will follow.

If a man sees himself in a dream plunging into the river: good, it means purification from all evil’. (McDowell, 1999).

Inauspicious dreams:

‘If a man sees himself in a dream seizing one of his lower legs: bad, it means a report about him by those who are yonder (the dead).

If a man sees himself measuring barley in a dream: bad, it means the rising of words against him.

If a man sees himself bitten by a dog in a dream: bad, he is touched by magic.

If a man sees himself in a mirror in a dream: bad, it means finding another wife.

If a man sees himself in a dream making love to a woman: bad, it means mourning.

If a man sees himself in a dream looking at an ostrich: bad, harm will befall him.

If a man sees himself in a dream feeding cattle: bad, it means wandering the earth.

If a man sees himself in a dream casting wood into water: bad, bringing suffering to his house’ (Quirke, 1999).

Some of the dream book’s interpretations are coolly rational;

‘If a man sees himself removing the nails of his fingers: bad, this means removal of the work of his hands’;

hand injuries were likely a frequent if unfortunate event and clearly a dreaded hazard for Deir el Medina artisans. Other interpretations are less easily explained;

‘If a man sees the gods making tears cease for him in a dream: bad, it means fighting.’

It is not known to what extent these interpretative guides were used in daily life. Few people would have had access to such texts; few people were literate and able to read them. There are indications that many villages may have had a priest, or a local scribe else who could interpret dreams in which deceased relatives or gods might appear. Some later New Kingdom Deir el Medina texts refer to ‘the wise woman’ of the village who supplied advice. Such ‘seers’ were consulted not only concerning dreams, but on other issues affecting daily life including disputes with neighbours, or concerns over failing crops. Dreams could be powerful experiences and revelatory dreams in particular, were taken seriously.

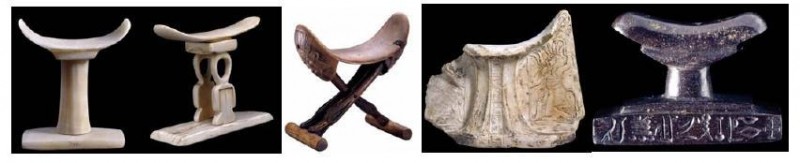

A timeline of headrests: Figure 11. Left to Right: 1. EA 29913, Old Kingdom, 2350 BC, Calcite: 2. EA 30727, Isis Knot motif, headrest, tomb of Gua, Deir el-Bersha, 12th Dynasty, Ivory: 3. EA 18156, Akhmin, late 18th Dynasty, around 1225 BC, Wooden: 4. EA 63783, Deir el-Medina, 19th Dynasty, 1225 BC, Headrest of Qeniherkhepeshef, official scribe, Limestone: 5. Amulet, H. 1.2 cms, L.2.4, Late Period, after 600 BC, Hematite. NB: The base of Egyptian headrests is usually wider than the top from the New Kingdom.

Qenherkhepesh helpfully provides us with the earliest, pre-Ptolemaic period hint that sleeping in or near a temple was conducive to soliciting assistance from deceased family members:

‘I have walked in the Place of Beauty. I have spent the night in this forecourt and drunk the water in the forecourt of Menet; it waters the plants and lotus-flowers in the forecourt of Ptah. My body has spent the night in the shadow of your face, beside the lords of Djeseret.’ (Quirke, 1992).

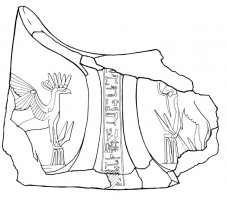

In this text from his funerary stele, the scribe refers to having slept in the forecourt of a shrine in the Valley of the Queens (the Place of Beauty) and likewise in the temple environs of Djeseret, the Deir el Bahri temple of Thutmosis III. Was the scribe attempting to commune with the deceased or with the gods through such acts, or was it an act of homage to sleep in such sacred settings? Figure 12.

Another villager from Deir el Medina claimed to have been instructed by the goddess Hathor, on where to construct his tomb. Although the inhabitants of Deir el Medina may have been atypical, with higher than average rates of literacy and living as they did in a specially constructed community, one wonders if their experiences were shared by others, higher or lower on the social scale. It appears to have been usual in this community, to seek the interpretation of dreams and to accept both negative and positive interventions by deities and the dead in the lives of the living.

By the later Dynastic periods, dreams which had religious significance appear to occur mainly in temple settings. Dreams become less personal experiences, perhaps reflecting the growth of urban communities, with greater access to temples for more people, particularly during annual festivals and processions.

Conclusion

We may not fully understand all the levels of meaning associated with the dead, the eternal sleep of the deceased or the ancient Egyptian interpretation of dreams. In Egyptian ideology, ‘complex areas of life and belief, of morals and loss, are never straightforward, any more than the gods are, but they are vital both to society and religion.’ (Baines, 1991). The ancient Egyptian understanding of the relationship between the living and the dead continues to captivate us as much as it occupied them, in life, in death and in their dreams.

Sleep and The Sleeping in Ancient Egypt by Barbara O’Neill is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial License.

Bibliography

Allen, J., 2005, ‘The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt’, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Baines, J., 1991, ‘Society, Morality and Religious Practice’, in B. Shafer et al, ‘Religion in Ancient Egypt; Gods, Myths and Personal Practice’, Cornell University Press, USA.

Caesarani et al, 2003, ‘Whole-Body Three-Dimensional Multidetector CT of 13 Egyptian Human Mummies’, AJR 2003;180:597–606, AJR Society, USA

David, R., 1998, ‘Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt’, OUP, UK

Faulkner, R. 1973, ‘The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts’, Aris & Phillips, UK

Forman, W., Quirke, S., 1996, ‘Hieroglyphs & The Afterlife’ University of Oklahoma Press, USA.

Lurker, M., 1980 (English Language Edition) ‘The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt’ Thames & Hudson, UK

McDowell, A., 1999. ‘Village Life in Ancient Egypt; Laundry Lists and Love Songs’, OUP, UK

Pinch, G., 1994, ‘Magic in Ancient Egypt’, British Museum Press

Quirke, S., 1992, ‘Ancient Egyptian Religion’, British Museum Press, UK

Roberts, A., 1995, ‘Hathor Rising; The Serpent Power of Ancient Egypt’, Northgate Publishers, UK

Szpakowska, K,. 2008, ‘Daily Life in Ancient Egypt’, Blackwell Publishing, UK

Teeter, E., 2011, ‘Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt’, Cambridge University Press, UK

Wilkinson, R., 1992, ‘Reading Egyptian Art’, Thames and Hudson, London

Image Credits

All images used with permission courtesy © British Museum unless stated:

Figure 1: Wooden Headrest, Dongola Reach, Kerma Classique Period, BM 55436

Figure 2: Wooden Headrest, 4th Dynasty, British Museum

Figure 3: Wooden Headrest, New Kingdom, Lahun, BM 47977

Figure 4: Tomb of Ramose, Burial Goods, Photo: Nacho Ares

Figure 5: Wooden Headrest, 6th Dynasty, Tomb of Khnumankh, Meir, BM 69249

Figure 6: Bes Detail, Wooden Headrest, New Kingdom, BM 51806

Figure 7: Headrest from Tomb of Tutankhamun, Photo: Nacho Ares

Figure 7a: As above

Figure 8: Bedroom Furniture, Thebes, New Kingdom, BM 18196

Figure 9: Mythical Beasts Detail, 19th Dynasty Headrest of Qenherkhepesh, British Musuem, EA 63783

Figure 10: Dream Book of Qenherkhepesh, P.Chester Beatty III, British Museum, EA 10683

Figure 11: Chronological Timeline of headrests, all courtesy of British Museum

Figure 12: Valley of the Queen, Photo: Nacho Ares

By

By