By Barbara O’Neill. Published on Egyptological, June 30th 2011, Edition 1.

Introduction

1. Cosmetics box, containing juniper berries, powered red ochre and a kohl stick, Wood, 12th Dynasty, Lahun, © Manchester Museum.

With a culture far removed in time and space from our own, why are aspects of Egyptian art both unexpectedly familiar and yet strangely exotic? Tomb scenes depict idealised individuals surrounded by personal belongings, which often includes mirrors and items such as cosmetic containers. It seems from the inclusion of such personal items that a ‘perfect’ appearance both in life and in death was of great importance to ancient Egyptians.

Why are mirrors and other cosmetic items so often depicted in the narrative imagery of tomb scenes? In the following article I will explore the significance of mirrors in tomb art, and their possible function in the afterlife of the deceased.

Early Mirrors and Developing Concepts of the ‘Self’

2. One of the earliest known mirrors, hand crafted from obsidian. Estimated to be around 8000 years old.

Small conical pieces of obsidian are known from prehistoric Turkey. The stone was shaped into small dark receptacles designed to hold water, thereby providing reasonable reflection. Highly polished and worked into a slightly convex form, these early mirrors were designed to sit upright on a small stand. Similar items made from polished stone may have been used in Predynastic Egypt, although no examples have yet been identified. In early Egypt most people would have viewed their reflection in water. It wasn’t long however before Egyptians, in their eternal quest for perfection, found a more efficient method of achieving reflection.

There is no evidence of metallic mirrors from Egypt’s Predynastic period. However, a highly polished selenite flake set into a wooden frame has been dated to the Badarian era (c. 4400 to 4000 BC) indicating remarkable ingenuity in the design of this early prototype. The fact that such early mirrors exist, is an interesting indication that a desire to view the self is evident from an early stage in Egyptian culture.

3. One of the earliest known sculptures from the predynastic Badarian culture, this figure is made from the lower canine tooth of a hippotamus and may have associations with sexuality and regeneration, © Trustees of the British Museum.

Today, it is hard to avoid images of oneself, caught in mirrors and in reflections from the modern world which surrounds us. In antiquity however, concepts of the self developed gradually through the prehistoric period until the Bronze Age, when implements including mirrors, tweezers and razors appeared almost at the same point in prehistory. These items were related to increasing individualism, self ornamentation and associated with changing aesthetics of the body.

flat grinding surface for the preparation of cosmetics and then used as a reflective surface in which to apply make-up. Experiments have shown that when the stone was washed and wetted, it would have acted as a good reflective surface. The water evaporated rapidly however, providing just a fleeting reflection. It is possible that oil rubbed on to the stone palette would have provided a more lasting reflection than water, although this method would have made the polished stone difficult to handle.

Anatomy of the Mirror

From the First Dynasty through to the New Kingdom and beyond, Egyptian mirrors usually consisted of three main parts. These are:

- the mirror disk with an integral tang, usually formed from copper or bronze alloys: silver is attested from the Middle Kingdom;

- the umbel, often integral to the handle, was formed from wood, ivory, bone, horn or metal alloys; and

- the handle, (in those mirrors found intact), which usually matches the materials used to form the umbel

Mirror parts were joined by wooden pegs wedged or cemented into place with the slit at the top of the umbel filled with adhesive securing the tang of the disk. On later mirrors, metal rivets were soldered into place, connecting the handle to the disk. The umbel developed into a more elaborate third part of the mirror’s design, sometimes crafted into a stylised head of a goddess, usually Bat or Hathor, although other deities including Sekhmet and Mut are also known. Male deities represented on umbels include Khonsu and Bes, although they are less commonly found on mirrors than female deities.

The main features in the design of the ancient Egyptian mirror were in place by the end of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1630 BC). By the New Kingdom, more mirrors, made entirely of metal appeared.

Dating and Design

commodity which came under direct Pharaonic control, hippopotamus ivory was cheap and readily available throughout Egypt. The hippopotamus continued to inhabit the Egyptian Nile Valley throughout the Dynastic era. With its gleaming white appearance and high density, hippopotamus tooth may have become the poor man’s ivory. Their incisors were the right dimensions for use as cylindrical mirror handles. Bone was another readily available resource; an easily worked material that polished up well for use as decorative inlay, or used to produce handles.

Obsidian, probably imported from ancient Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia and Eritrea) is another material found in Egyptian mirror handles dated to the Middle Kingdom; with a beautiful Twelfth Dynasty example found in the treasure cache of Sithathor-iunut, a daughter of Senwosret II, discovered amongst other precious items in her tomb at Lahun.

Autobiographical or other inscriptions (datable to the reign of a specific king) sometimes occur on mirror disks and handles. Some mirrors are inscribed with personal names or titles which can be dated to a particular era. In the case of the royal butler, Kemeni, his beautiful cosmetic box complete with a number of small stone pots, also contained the mirror of another man; an official of the

same era named Reniseneb. The cosmetic box and the mirror are both dated to the Twelfth Dynasty. The mirror is inscribed for Reniseneb, who lived during the reign of Amenemhat IV. This inscription also includes his title, ‘Great One of the Tens of Upper Egypt’, reference to a now obscure administrative position. Reniseneb’s exquisitely crafted bronze mirror, has an ebony handle inlaid with gold. Intriguing questions remain as to whether the King’s butler Kemeni and Reniseneb were related, and why did one man’s mirror end up in another man’s cosmetic box? Kemeni’s toilet box is not the only example of a man owning such an item and indicates that an interest in personal grooming was shared by both males and females.

The painted record is useful in dating actual mirrors through style and geographical location. Painted mirrors are found on the ‘frieze of objects’, (a narrow band filled with a wide range of items), placed on the inside and sometimes on the outer surfaces of coffins dated to the Middle Kingdom. The ancient Egyptians believed that objects painted on coffins, or within the tomb itself, would become accessible to the deceased in the afterlife.

As noted earlier, many New Kingdom mirrors are formed entirely from metal, although wooden, stone, ivory and bone handles continue to be produced through this era and beyond. Along with the ‘Hm’ style handles discussed above, mirror handles are also designed as papyrus or lotus stalks and painted green or brown to reflect the plants they represent. Both plants were symbolic of rebirth in the afterlife. It is also in the New Kingdom, that the motif of a nude female figure forming the mirror handle becomes popular, though metal mirrors with this motif began to appear in the late Middle Kingdom. In terms of dating Egyptian mirrors, it is usually an accumulation of associated evidence from geographical location if known; materials used and stylistic motifs employed, all of which combine to produce a reasonably firm date.

Mirrors, Make-up and Messages

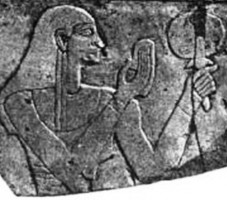

12. Lady of the House Ipwet using a mirror as she applies unguents or cosmetics, © Trustees of the British Museum

Mirrors are often found in association with cosmetic implements and containers. Toiletry items associated with mirrors in burials throughout the Dynastic era include hairpins, combs, eyeliner applicators, cosmetic spoons and both kohl and ointment containers. These items have been found in the burials of both men and women, indicating that cosmetics were used by both sexes. Cosmetic use is believed to have functioned on four levels: aesthetic, hygienic, therapeutic and in religious contexts. Kohl compounds made from malachite and galena, a mineral used in ancient Egyptian eye-paint, have some antibacterial and sun screening properties. The crude forms of malachite and galena have been recovered from tombs, where they were stored in small linen or leather bags, ready for final preparation in the afterlife. Bags of green and black ‘eye paint’ appear on the offering lists of Djau, an Overseer of Priests under Pepy II, recorded in his tomb at Deir el Gebrawi near Asyut. Cosmetic powders have also been recovered from the tombs of men and women at Deir el Medina in Upper Egypt. Many other concoctions were used in cosmetics, often combined with animal fats as binding agents.

The application and wearing of makeup has been described as ‘an erotically charged activity’, as indicated in the Turin Papyrus, (Meskell, 2002). This papyrus contains various images of sexual activity in one of which a woman is shown holding a mirror, as she carefully applies her make up! Cosmetic use by Egyptian men and women has been described as an act which transformed individuals into a uniformity of perfection, where even the sexes may have been hard to distinguish. The significance of applying cosmetics to the face and the body has layers of complex meaning in many ancient cultures. The preparation and application of cosmetics was costly and time consuming, restricting the most elaborate use to elite members of society.

Egyptian poetry, sometimes referred to as the ‘archaeology of the emotions’, carries ‘messages’ about ancient life that allows limited insight into the past. Within this literary genre, there are many references to mirrors, ointments and cosmetics. In a hymn to Hapy, a fecundity deity associated with the inundation, we learn that at times of drought, ‘cloth is wanting for one’s clothes, noble children lack their finery; there’s no eye-paint to be had and no one is anointed’, (Lichtheim 1973). The maiden in a New Kingdom poem states, ‘I wish to paint my eyes, so that if I see you my eyes will sparkle’, (McDowell, 1999). This poetic imagery is supported by modern chemical analysis with the discovery that the granular properties of galena provided the make-up with a glistening, metallic brightness.

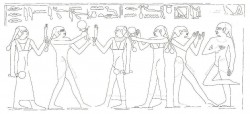

Mirrors are held by women or their female attendants in hair-dressing scenes, the encoded imagery of which is as close as it gets to eroticism in ancient Egyptian art. Female hair had erotic significance, marking women as icons of sexuality and fertility. Hair dressing scenes are thought to reference these aspects of sexuality, fertility and regeneration. In image 13, a detail from the Eleventh Dynasty sarcophagus of Kawit, a consort of Mentuhotep II, both the princess’ and her hairdresser’s hands form the hieroglyphic determinative for ‘hair’ or ‘hairdresser’, combining textual elements within this symbolic image. Perhaps aspiration for perfection in life and in death is a key element of why mirrors feature so prominently as a desirable item in the afterlife.

Ownership and Association

A curious anomaly noted by many scholars concerns gender and mirror ownership. We know that mirrors were owned by and included amongst the tomb goods of men, women and children. However, late Victorian and early 20th century excavators, uncertain as to whether the mirror-owning tomb occupant was male or female, often assigned gender by reference to other items found within the burial. Gender identification errors are common in burials containing mirrors alongside ritual knives, daggers or other items deemed masculine, causing the deceased to be erroneously declared male, when no other indicators of gender were present. Similarly, the occupant of tombs containing toiletry items and mirrors were sometimes mistakenly understood to be female; closer anatomical examination has refuted this. Ultimately, mirrors are not an accurate indicator of gender within Egyptian burials.

Representations of mirrors occur in the tomb art of both males and females. Ownership of mirrors by men is more prevalent in the Old Kingdom and in the early Middle Kingdom. However, most scholars agree that from the late Middle Kingdom, throughout the New Kingdom and beyond, mirrors are predominantly associated with women. Mirrors may have symbolised different concepts for either gender, though the distinctions are not clear. What does seem certain is that mirrors are rarely shown before the face of a man, held by a man or carried in offering scenes by male servants. Intriguingly however, mirrors are represented just as frequently on the ‘frieze of objects’ painted on or within male sarcophagi or coffins, as they are on female coffins.

The position of mirrors found in situ varies. Although some mirrors found in Early Dynastic burials were placed in the hands or by the feet of the deceased, most mirrors were positioned near the face, beneath the head or near the shoulders of men and women throughout the Dynastic period. Encased mirrors are often associated with sandals, matting and other high value burial goods. Free-standing or hand-held mirrors are associated with a range of objects including jewellry, head-rests, linen and ointment jars.

Religion and Mirrors

Mirrors are associated with priestesses in the cult of Hathor from the late Old Kingdom and throughout the Dynastic era. In the Middle Kingdom, at least six wives of the Eleventh Dynasty king, Nebhepetre Mentuhotep, buried within chapels beneath the king’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri, hold priestess titles associated with the cult of Hathor. One of Mentuhotep’s wives, who bore the title ‘royal ornament’, indicating both her religious role and favoured status, was buried with two mirrors. Another of the king’s consorts, Neferu, thought to be a sister-wife of the king and one of the first females to bear the title ‘mistress of the household’, had several representations of mirrors in her tomb, some of which were inscribed with the king’s name. Many of these mirrors have umbels shaped as stylised heads of Hathor, or bear Hathoric symbolism on the handles. Other goddesses were represented on mirrors. Many have close association with Hathor, including the goddesses Wadjet, Sekhmet and Mut. With only two exceptions known, inscribed mirrors for men rarely include priestly titles. Those that do are engraved with the name and title of a lector priest (who read sacred texts or performed ritual in the temple) and with the name and titles of an overseer of priests.

Another popular mirror form which appeared towards the end of the Middle Kingdom was the ‘divine standard’ design, usually accompanied by single or double horus falcons. In this form, the mirror disk may have represented the solar deity Ra; the sun god who ensured eternal renewal for the deceased in the netherworld. The divine standard motif, with single or double horus-falcons, continued as a popular mirror design throughout the Pharaonic era.

Mirrors painted in burial chambers or on coffins sometimes have red disks thought to represent the sun. Other mirror disks are painted white, perhaps referencing lunar deities. Red and white forms are sometimes found in pairs, within the same scene. The range of colours used to represent mirror disks, includes red, yellow and white. Complex iconography may have influenced the range of materials used to produce mirrors, with copper and bronze disks associated with solar deities, and rarer silver mirrors related to lunar symbolism. An unusual silver-disked mirror with an umbel representing Khonsu, would appear to confirm this lunar association.

In the New Kingdom, mirrors are closely associated with fertility and childbirth. It is from this era that mirror handles in the form of Bes, first appear. Bes was a domestic deity with close associations with women and children. His image is often found on household items, as well as on magical wands and ritual knives associated with childbirth.

An Object of Desire

Mirrors are often indicators of status in Egyptian tomb art. Labour intensive production meant that even mirrors made from wood and polished stone would have presented considerable effort and economic output. The mirror’s symbolism as a sign of elite status, is supported within Egyptian literary sources. Descriptive lines in the ‘Admonitions of Ipuwer’, a lament composed in the Middle Kingdom, which looks back to the trials of the First Intermediate period (c. 2125-2010 BC) indicates something of how mirror ownership was perceived by the Egyptians themselves,

“Behold, she who had no box is now the owner of a coffer,

And she who had to look at her face in the water is now the owner of a mirror”, (Parkinson, 1997).

Although the retrospective lament of the ‘Admonitions’ appears to associate mirrors with elite society, it is important to note that mirrors have also been found in domestic settings, including the workmen’s village at Lahun and from very simple graves, including those of children.

What’s in a name?

So why did Egyptians include mirrors amongst burial goods in royal, elite or humble tomb settings? The functionality of mirrors can best be described as multi-dimensional and it seems clear that apart from a cosmetic value, there were symbolic meanings attached to mirrors within the funerary context. The complexity of this symbolism is indicated in the terminology used in association with mirrors.

regeneration and fertility were paramount. The phrase, ‘anx-mAA-Hr’, literally ‘mirror that sees the face’, is the term most often used in association with painted representations of mirrors. In some cases the word ‘pr’ or ‘house’ is used with ‘anx’ in mirror labels, suggesting a domestic use for certain types of mirror. Poignantly, other labels refer to ‘a mirror for use during the course of the day’. The range of terminology used to describe different types of mirror provides a fleeting glimpse into ancient domestic arrangements. Perhaps sturdier mirrors were placed in rooms where cosmetic application or hairdressing was carried out, with more finely crafted mirrors reserved for ritual purposes.

Although the term ‘anx’ was used to describe free-standing, encased and hand mirrors from the Middle Kingdom onwards, mirror nomenclature evolved for particular types of mirror. Five mirrors from Middle Kingdom Bersheh are labeled, ‘mirror in its house’, referring to their elaborate casing. Other mirrors from Bersheh are named, ‘the excellent one’, and ‘the divine one’. Whether this relates to the mirrors or is in reference to the owners is unclear!

By the late Middle Kingdom, such fine distinctions are less frequently found in mirror labels, with all types of mirror mostly referred to simply as, ‘anx’.

The label, ‘anx mAA Hr’ (“a mirror to see the face”) was used in all periods to describe different types of mirror, including encased mirrors, free-standing mirrors and hand mirrors of ‘divine standard’ or Hathoric design.

Capturing Eternity

The concept that the mirror actively ‘saw’, rather than simply reflected a living image, occurs early in Egypt. The mirror’s capacity to observe and to ‘see’ the face, capturing and maintaining the essence of the person reflected, is a conceptual variation which takes us into the ancient Egyptian mindset in a world we cannot easily comprehend. On some mirrors, the eye-sign, Gardiner’s D4used in the label ‘anx mAA Hr’, (‘a mirror to see the face’), is drawn onto the disk or handle, forming the phrase, ‘one who sees the face’, ‘face seer’ or ‘one who sees Ra’. Amuletic wadjet eyes drawn on to paintings of mirrors seem to support this complex connotation.

mirror, in order to hold it there for eternity. The accompanying text reads, ‘the beautiful name of Hathor, the hand of Atum’, a reference to Hathor’s crucial role in the regeneration of Atum, an early creator god.

Other references to creation and renewal continue within the scene through the presence of harpists, who play before the dancers. The harp is associated with intimate love songs and with the act of creation.

Conclusion

It is clear from this discussion that there is a broad range of meaning encoded within the ancient Egyptian mirror, and that it was desirable to possess one in the afterlife. While the symbolism bound to these ‘objects of desire’ is not fully understood, the range of ritual actions associated with mirrors includes regeneration of the deceased, conservation of the appearance, a means of capturing and maintaining important ritual and as a depository of the soul.

With their complex iconography merely touched upon in this article, the next time you have the opportunity to stand before a display case filled with dulled, ancient mirrors, take a moment to consider the reflections captured within these once shining disks; reflections of Egypt thousands of years ago.

Reflections of Eternity by Barbara O’Neill is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial License.

For a useful chronology of Egyptian mirrors from the Old Kingdom to the Roman era see: http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/metal/mirrors.html

Bibliography

Assmann, J., 1996, ‘The Mind of Egypt’, Harvard University Press

Aston, B., Harrell, J., Shaw, I., 2000, ‘Stone’, in P. Nicholson and I. Shaw eds, ‘Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology’, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Bird, J., 1986, ‘An inscribed Mirror in Athens’, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 72, pp. 187-189

Cotte, M., 2005, ‘New Insight on Ancient Cosmetic Preparation’, in Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume 553, November 2005.

David, R., 1998, ‘Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt’, OUP

Hodder, I., 2000, ‘Agency and Individuals in Long Term Processes’, in M. Dobres and J. Robb, eds., ‘Agency in Archaeology’, Oxford, Routledge.

Kanawati, N., 2006, ‘Recent work in the Tomb of Djau at Deir el-Gebrawi’, in S. Binder et al, eds, ‘The Bulletin of The Australian Centre for Egyptology’, 2006, Macquarie University, Sydney.

Krzyszkowska. O., Morkot, R., 2000, ‘Ivory and Related Materials’ in P. Nicholson and I. Shaw eds, ‘Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology’, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Lilyquist, C., 1979, ‘Ancient Egyptian Mirrors from the Earliest Times through the Middle Kingdom’, Berlin, Munchner Agyptologische Studien Heft 27

Manniche, L., 1999, ‘An Ancient Egyptian Herbal’, British Museum Press

Martinetto, P., Dooryhee, E., et al, 1999, ‘Cosmetic Recipes and Make-up Manufacturing in Ancient Egypt’, L’Oreal Recherche, Clichy, France.

Meskell, L., 2002, ‘Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt’, Princeton University Press

Naville, E., 1910, ‘The Eleventh Dynasty at Deir el Bahri’, London

Ogden, J., 2000, ‘Metal’, in P. Nicholson and I. Shaw eds, ‘Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology’, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Parkinson, R., 1997, ‘The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Ancient Egyptian Poems, 1940-1640 BC’, Oxford, OUP.

Petrie, W.M. Flinders, 1927, ‘Objects of Daily Use’, British School of Archaeology in Egypt, London

Szpakowska, K., 2008, ‘Daily Life in Ancient Egypt’, Malden, Blackwell

Watterson, B., 1991, ‘Women in Ancient Egypt’, Gloucestershire, Sutton Publishing

Photo Credits – used with permission

Figure 1: Cosmetic Box, EGY 75, Manchester Museum

Figure 2: Neolithic obsidian mirrors, Museum of Anatolian Civilisation, Ankara, Photo by P. Gorgori

Figure 3: Badarian fertility figure BM EA 59648, Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

Figure 4: Stone Palette, Naqada II, EGY 4592, Manchester Museum

Figure 5: Mirror, Athens. Diagram by Barbara O’Neill, photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 6: New Kingdom Mirror, Cairo. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 7: Ivory mirror handle, Bolton Museum

Figure 8: Early New Kingdom Mirror, EGY 5591, Manchester Museum (Not shown in feature).

Figure 9: Twelfth Dynasty mirror of the Princess Sithathor, Cairo.

Figure 10: New Kingdom ‘Hm’ handled mirror, BM 22830, Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

Figure 11: Middle Kingdom mirror of Reniseneb, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Figure 12: Lady of the House, Ipwet, British Museum.

Figure 13: Kawit hairdressing scene, Cairo Museum. Photo by G. Tassie

Figure 14: Hathor mirror, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 15: Bes Mirror Handle, Nineteenth Dynasty. Photo by P. Gorgori

Figure 16: Divine Standard Mirror, BM 2731, British Museum

Figure 17: Yellow painted mirror, Tomb of Renni: El Kab 7, Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 18: Twelfth Dynasty Mirror, Lahun EGY 189, Manchester Museum

Figure 19: Metal mirror, provenance Aswan, Brooklyn Museum NY. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 19a: Sturdy Mirror, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 20: Mirror Case Tomb of Tutankhamun, Cairo. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 21: Encased mirror under chair, el-Kab, Tomb of Renni. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 22: Ivory Hathoric Wand, Brooklyn Museum, NY. Photo by Nacho Ares

Figure 23: Mirror capturing ritual action, Tomb of Mereruka after Lilyquist, 1979

Figure 24: Egyptian Mirrors, Louvre Museum, Paris. Photo by Janmal, amended by Barbara ONeill

PDF Version

If you wish to see a slightly extended version, with references but without images, please see the following PDF: Reflections of Eternity

Biography

Barbara O’Neill is an online student of Egyptology with the University of Manchester. She has lived and taught in Egypt and the Middle East, where she still resides.

By

By